I feel embarrassed writing this piece because I did not put the hard work in. I merely began reading Orhan Pamuk’s book Istanbul: Memories and the City. In it, he created such a vivid image of his hometown that I wanted to see that Istanbul for myself. With just three days to spend there, I tried to balance visits to the popular monuments with walks in the neighborhoods that Pamuk referred to in his book.

On the other side of the Galata Bridge

I stayed in the Tophane neighborhood. The famous sights of the Hagia Sophia and Topkapi Palace remained on the other side of the Galata Bridge, but I could easily reach them by tram. In Tophane, I relished being so close to the neighborhoods from the book, where mostly locals go.

I found it intriguing that Pamuk’s Istanbul did not revolve around sultans, mosques, harems, and bazaars. He considers those a Western, exoticized version of the city. Instead, his Istanbul languished around the mid-twentieth century. The fall of the Ottoman Empire still haunted the living memory, but the rapid modernization had not yet begun. For Pamuk, there was an air of decline hovering over the city. The new country had become a republic, and, unsure of its identity, it attempted to embrace everything Western.

I walked through the neighborhoods I learned about in his book — Galata, Çukurcuma, Cihangir, Taksim, and further out, Nişantaşı, where Pamuk grew up. Aside from the ever-dominating Galata Tower, the neighborhoods do not have spectacular structures. But they give the city its character and life. They are made of busy narrow streets, with residential buildings old and new. The ground floors have shops and cafes. Many streets involve strenuous walks up and down, sometimes with views of a mosque or the Bosporus on the horizon. The occasional garden in the middle of a block provides a green respite from the sultry summer city.

It was intriguing to come across rare wooden houses that had not been remodeled for decades. In Pamuk’s book, they are one of the main characters. The city of the mid-twentieth century saw them as eyesores; the marks of the decline, which should be eradicated as quickly as possible. Now only a few remain. They stand out as the last witnesses to the past, waiting for their upgrade or destruction.

The People of Istanbul

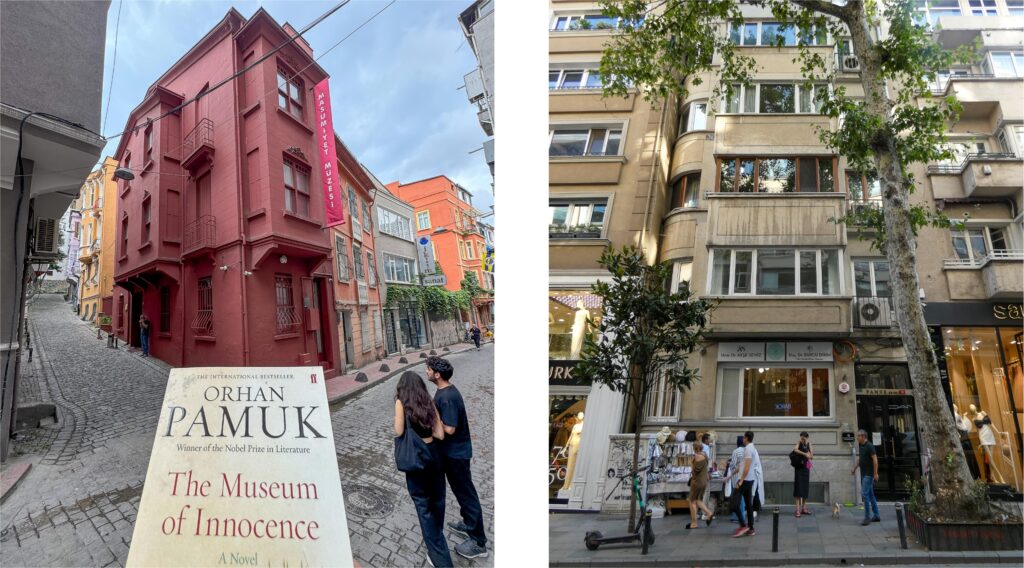

In Çukurcuma, I went to the Museum of Innocence, a small cultural center created by Pamuk to accompany his eponymous Nobel Prize-winning novel. The museum resides in a painted wooden house, and it won the 2014 European Museum of the Year Award. It contains artifacts that follow the story of the novel but also bring to life the city of the past century. There is a dress, old photographs, a bed, a bottle of the first Turkish soda, a lot of cigarette butts, and documents from a healing stay in a yalı — an important term, which refers to an old, water-front mansion on the Bosporus outside Istanbul.

Next to the museum is one of the old wooden houses in its original state, which had a cat sitting on its fence. An older gentleman, who was just walking into the house, saw me taking a picture. He pointed to the cat and said: “Pamuk.” That was the only time a local referred to the writer unprompted. The museum visitors were exclusively coming from abroad, which made me worried that reading Orhan Pamuk became a hipster fad, despite his 2006 Nobel Prize in literature. But that worry disappeared when I opened his novel The Museum of Innocence, which I just bought in the museum shop. As with the Istanbul book, I saw beautiful writing. The smoothly flowing, simple words, which form a strong current that draws readers into the story.

Still, Pamuk’s appreciation within Türkiye feels different. When I spent time with locals at a café at Taksim Square, a young lady responded to my question: “Pamuk? The Turkish people don’t read him that much. Mostly foreigners do.” I smiled at how similar his fate is to other writers, such as Kafka or Kundera, who are rarely admired among fellow Czechs.

Pamuk is well aware of the reasons for the disconnect — his books refer to his wealthy, business-owning family with real estate around the city. They would often travel to the West before it became common for everyone. I walked past his childhood apartment building, about which he extensively writes in his Istanbul book. It was still adorned with a “Pamuk Apartments” sign. The surrounding Nişantaşı neighborhood used to be just well-to-do, but now, it morphed into an upscale corner of the city, with boutique shops and exclusive restaurants. The only reminders of the old times are the street vendors selling simits, the ubiquitous Istanbul bagels.

The city is now so different from the mid-twentieth-century era that Pamuk describes. Since then, its population has exploded fourteen-fold! Suburbs have sprawled in all directions, and long metro lines keep getting longer. Of the locals I met at the café at Taksim, none was born in Istanbul. All moved there as young adults, from Turkish towns near and far. Then there are communities of expatriates in the city, immigrants from the West and the East.

Palaces of Istanbul

The story of Pamuk’s Istanbul begins in the nineteenth century when the Ottoman Empire found itself on the path of decline. The sultans decided to Westernize themselves and the Empire, which they saw as the only way to keep up with the West. Nowhere is the shift more visible than in their palaces.

I ended up visiting Topkapi Palace, the old fortress-residence of the Ottoman sultans with a harem and halls filled with Islamic ornaments and divans. My main motivation, however, was to contrast it with Dolmabahçe Palace, built by the nineteenth-century sultans as their modern and comfortable home. The rooms in Dolmabahçe are also majestic, but they resemble Western palaces, with French-style golden armchairs instead of divans.

Even the façades and porticos of Dolmabahçe are thoroughly Western. What makes the palace unique is its airy location right on the Bosporus, with gardens that are separated from the blue waters only by the ornate fence. It is the most pleasant spot for a refreshing walk in the city.

On the Bosporus

I traveled outside the city to retrace what Pamuk describes as the usual weekend Bosporus trip. I took a bus along the strait, all the way to the fortress of Rumeli Hisarı. The fortress rises along a steep slope from the water promenade. It was built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, in 1452, as a security checkpoint on the Bosporus before his final assault on Constantinople. Pamuk refers to the canons exhibited at the fortress, which he admired as a boy.

Some of the immense compound was being renovated, but I could still climb a few trails inside it. The scenery was spectacular, with the massive round towers below me, the Bosporus at its narrowest right behind them, and the 1985 suspension bridge in the background, connecting the hills on both sides of the strait.

One could watch for hours the summer blue skies, the greenery, and the busy maritime traffic on the water. No wonder that apart from being a weekend destination, the slopes of the Bosporus became favored places by the Istanbul elite to build wooden houses and yalıs. Pamuk decried their later neglect and destruction, but many of them have survived and I managed to find one example near the fortress — the House of Tevfik Fikret. He was an early-twentieth-century poet and painter, who designed his house at the spot with perfect views. Today, it is a museum that preserves the poet’s memory — his tomb is in the garden — and gives us another glimpse into the lost era that Pamuk recreates in his books.

At the waterfront, I walked past a row fisherman, and then I noticed local men lounging in their swimwear around a rusty ladder leading into the water. This was not a prime Mediterranean beach, but I could not resist and followed them to take a swim. I did not care about the tankers that were passing behind our backs because the water was just too refreshing in the summer heat. Not having a towel did not worry me either. I dried easily as I kept walking along the shore until the resort town of Bebek, where I boarded a ferry back to Istanbul.

From the ferry, I saw how both sides of the strait were developed, with new houses lurking in the forest. Pamuk says this is “the ugly construction that would crop up over the next forty years” since his childhood. To eyes that have witnessed abrupt over-development around the world, it does not look all that bad.

The sun began to set as the ferry approached the city. Even though I promised myself not to fall for the exotic of Istanbul, I could not help myself at that moment. We passed by several beautifully remodeled yalıs, and then by the Ortaköy Mosque, proudly showing its Ottoman decoration against a much taller modern bridge. The city became darker as the sky turned orange. The silhouettes of mosques interspersed with towers and high rises covered all the shores and hills of the city. That was a beautiful illustration of what Istanbulites say — the city does not have one dominating central district. Each neighborhood thrives on its own.

Modern Istanbul

Back in my neighborhood is Tophane Square, the latest blend of the Ottoman and the modern. One of its sides has the traditional Ottoman fountain, a mosque, and an ornate clock tower; all with rejuvenated looks. That way, they withstand the stark contrast with the sprawling glass creation on the other side of the square — the Istanbul Modern Museum, opened in 2023.

Istanbul Modern houses paintings by modern Turkish artists. But interestingly, they also had an exhibit of black-and-white photographs of life in Türkiye from decades ago. I walked through the gleaming minimalist rooms of the new museum, looking at photographs of a villager’s family riding on a single donkey, a peasant plowing a field, or a child in front of a disintegrating wooden house in Istanbul. It reminded me that Pamuk’s Istanbul book also contains black-and-white photographs of the city from that bygone era. Actually, the collection of his photographs was the impetus for Pamuk to write the book. Modernity came to Türkiye, but the memory of life before its arrival has a strong hold on the country’s culture.

The front of the museum faces directly the Bosporus, and the top floor has a terrace to appreciate the views. When I was leaning against the railing, looking at the city, I could not bring myself to feel the mood of Pamuk’s book, nor that of the photographs downstairs. They often capture discomfort, wintery scenes, and a certain kind of melancholy, which Pamuk refers to as hüzün. Maybe because I went during the summer, maybe I still saw the city as just another tourist, or maybe the last few decades of development changed things, but the city came across as youthful, dynamic, and upbeat to me; despite the challenging politics which the locals bring up quite openly.

A delightful place to spend time in

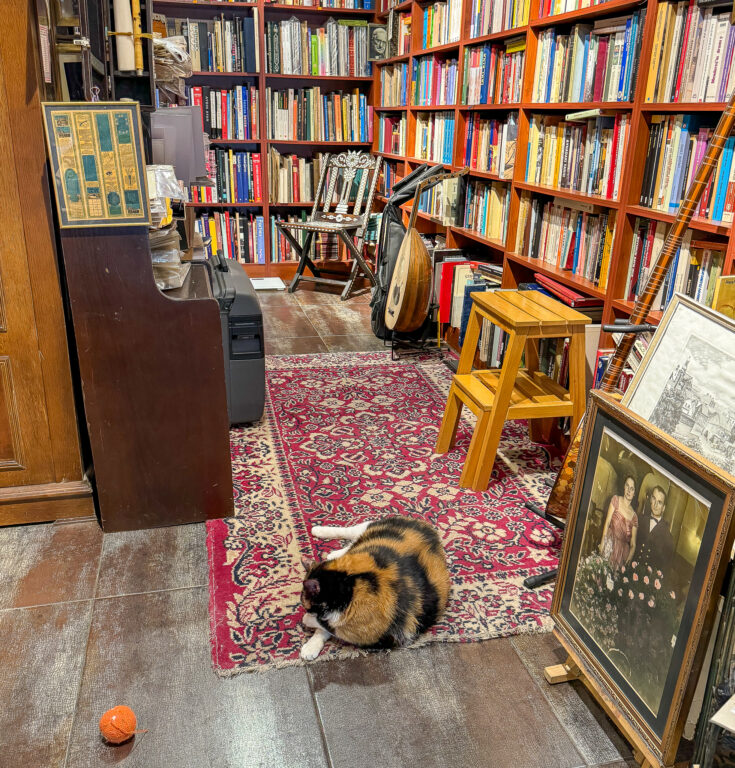

On my last walk through the residential streets, I stopped by a neighborhood bookshop that had a cat in its emblem. There were real cats running among the overflowing bookshelves too — in fact, cats rule the city these days, with the stray dogs from Pamuk’s book becoming more of a rarity.

I smiled when I noticed that the bookshop sells black-and-white photographs. But I bought a poster there instead, and as the lady was packing it for me, she offered that I rest on their sofa and have some tea in the traditional ince belli glass. Sipping on it and seeing young people strolling behind the window only reinforced the impression I got from exploring the city. Istanbul is not only a beautiful collection of monuments from the past. It is also an incredibly delightful city to spend time in.

If you go

South of the Galata Bridge: Hagia Sophia https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/ayasofya; Topkapi Palace https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/topkapi

North of the Galata Bridge: Galata Tower https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/galatakulesi; The Museum of Innocence https://www.masumiyetmuzesi.org/en; Istanbul Modern https://www.istanbulmodern.org/en; Dolmabahçe Palace https://www.dolmabahce-palace.com/

Around Bebek on the Bosporus: Rumeli Hisarı fortress https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/rumeli; House of Tevfik Fikret http://en.besiktas.bel.tr/entry/tevfik-fikret-museum/;

This article was previously published on TravelExaminer.net, where you can view dozens of award-winning national and international travel destination articles.