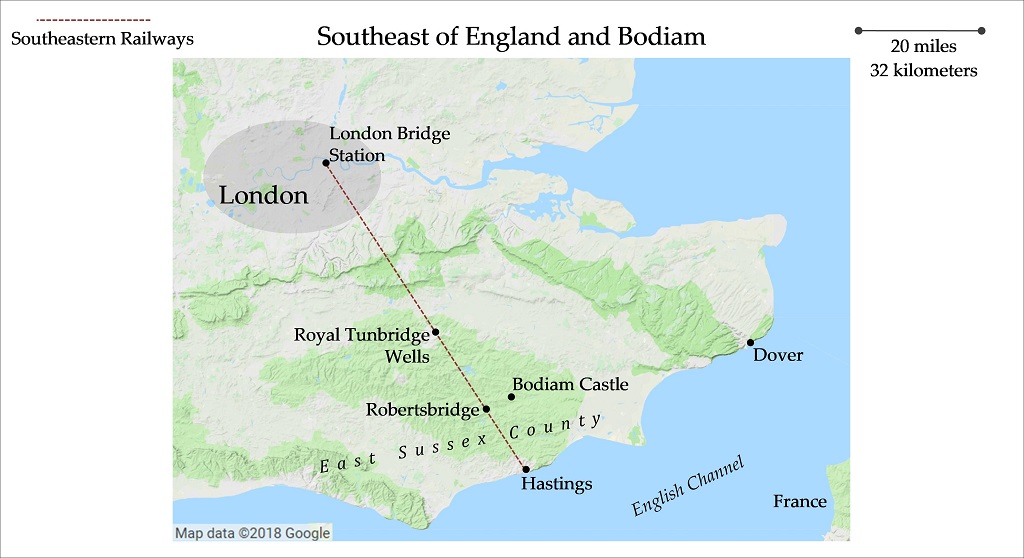

Bodiam Castle, England. About 55 miles (90 kilometers) south of London.

In 1385, Sir Edward Dallingridge probably did not expect that his creation would come up on Google lists of the top English castles. Or did he? Historians still debate what this not-very-prominent knight was really up to when he built Bodiam Castle.

Casual visitors often ponder the same question. But before they get to the pondering, they usually stare in awe at this partially restored ruin for a while, describing it as “the most visually striking castle in England,” “a fairy-tale castle,” or use some other understated phrases.

I know that I am running the risk of condemning this article to obscurity by not debunking any conventional wisdom, but I actually agreed with all those sentiments when I was standing in front of the landmark one chilly October afternoon, during my visit to England.

Bodiam has a squared plan, with a 180 ft (or 55 m) long side, round towers in its corners, crenellation on the top, and—most importantly—a large moat, which surrounds the entire castle. Is it any wonder that this symmetric elegance, which reflects itself in the water and therefore makes life easy for dreamy photographers, gets all kinds of fairy-tale adjectives?

The land of castles, horses, and politeness

The castle lies in the East Sussex county, south of London, on the banks of the tiny River Rother, not too close to any major city, railway hub, or highway—and that was a blessing for me. At least I did not have to fight for the best views with busloads of tourists. The only visitors I encountered were English families with kids playing knight games.

This remoteness meant, however, that I had to figure out how to get there from London, where I had just landed, without having to rent a car. I ended up taking a train to Royal Tunbridge Wells, and there, in front of the station building, I asked a lady in a waiting taxi to take me to Bodiam.

She might have been in her fifties, sporting short blond hair, and radiating English politeness to the degree that I was afraid, at first, to ask any question because it could spoil the atmosphere in the car.

Bodiam’s courtyard, with the Chapel and the owner’s private quarters on the other side. ©Libor Pospisil.

Those fears of mine turned out to be unfounded as she gladly began to talk to me about her life in an English village.

She said she lived on her own and recently fulfilled her biggest dream of buying a horse. Even though she did not express any vivid emotions, I could not miss the passion in her voice when she was describing how the everyday feeding, riding, and caring for her horse created a deep bond between the two of them, a relationship impossible with any other animal.

After I, as a foreigner, indicated my surprise that a taxi driver would own a big manor with a stable, she smiled, shook her head, and gave me a crash course on how the very English institution of shared village stables works.

Her stories brightened up my jet-lagged face because they made realize that I found myself in the world of my favorite British columnist, the Spectator’s Melissa Kite, who writes, with the typical English dry humor, about her adventures of settling down in an English village.

Standing at Bodiam Castle. I tried to dress up in the proper English way—no old California t-shirt. ©Libor Pospisil.

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire—a medieval edition

After the half-an-hour ride, I had to unfortunately end the conversation because we arrived at Bodiam and my attention turned to another English story: the life of the castle’s creator, Sir Edward Dallingridge (1346-1393).

Sir Edward came from a family of the lesser gentry, which makes it even more curious why and with what resources he managed to build such a castle. Through a convenient marriage, he obtained some land, including Bodiam. Through his military service, he earned the title of a knight. But what helped him most was a seminal conflict that shaped Western Europe of his era, known as the Hundred Years’ War.

That war pitted England against France over the claims of the English kings that they owned parts of the French territory and, at times, even the French throne. The French kings claimed, on the other hand, that the English kings were their vassals.

One of the English war campaigns on the French soil was conducted by a private army, under the infamously brutal knight Robert Knolles. As it happened, Sir Edward took part in that adventure. The knights conquered several French towns, earned the gratitude of the English king along the way, and, crucially, amassed handsome fortunes, even if some of it came from plain pillaging and ransom for kidnappings.

Bodiam Castle: how could a low-level aristocrat manage to build himself a fairy-tale castle? ©Libor Pospisil.

Upon his return back to England, Sir Edward’s standing continued to rise as he became a member of parliament. Another step on the social ladder for him would have been owning a castle. That presented a challenge, however, because he remained a low-level aristocrat, despite the war honors he received and his newly found fortune.

His unrelenting desire to enter the club of the most prominent English families concentrated his mind and he came up with a plan to ask the king for permission to build a fortified home for himself. The case he put to the king was that Bodiam lay between England’s south coast and London, right along the route that the French might use if they decided to invade England. Building a castle there would therefore contribute to the defense of the country.

That argument persuaded the king, not least because the scenario seemed all too real. When Norman forces of William the Conqueror invaded England, they passed through a town of Robertsbridge, near Bodiam, on their march to London in 1066. More recently, in the 1370’s, French ships barraged English coastal towns, mere 10 miles (16 kilometers) away from Bodiam. King Richard II therefore issued the following license:

…Know that of our special grace we have granted and given licence on behalf of ourselves and our heirs, so far as in us lies, to our beloved and faithful Edward Dalyngrigge Knight, that he may strengthen with a wall of stone and lime, and crenellate and may construct and make into a Castle his manor house of Bodyham, near the sea, in the County of Sussex, for the defence of the adjacent country, and the resistance to our enemies … In witness of which etc. The King at Westminster 20 October 1385… (Excerpt from the license to crenellate, allowing Edward Dallingridge to build a castle. Source: Patent Rolls of 1385–89).

Gatehouse—the main entrance into the castle. The coats of arms above the gate belonged to Sir Edward, his wife, and their relatives. ©Libor Pospisil.

Little did the king know that instead of fortifying any manor house, Sir Edward would build a moated castle from scratch. Not only could he afford it, but he also proudly reminded everyone of the origins of his riches by placing Robert Knolles’ coats of arms on the postern tower of the castle.

Luxury measured in fireplaces

I entered the castle the only way possible, by crossing the bridge over the moat and passing through the Gatehouse. Then, I found myself in the courtyard with a perfectly manicured lawn—yes, this is England. The buildings around the courtyard lay in ruins, however, since the English civil war of the 17th century when the parliamentary forces destroyed the castle. The ruins went unnoticed for a long time.

Spiral staircase in Bodiam Castle. A plaque warned that physically unfit visitors may have difficulties—they should have included tall visitors too. ©Libor Pospisil.

Only the early 20th century owner, Lord Curzon, commissioned a partial renewal of the castle by restoring the exterior walls and cleaning the ivy that had overgrown on the courtyard. On his deathbed, Lord Curzon donated Bodiam to The National Trust, which owns the castle to this day.

The only preserved interior spaces of the castle were the guard rooms and steep, narrow spiral staircases, which I climbed in the hope of getting great views from the tops of the towers.

The panoramas looked indeed as if someone had arranged them to resemble a stereotypical English countryside: meadows, sheep, villages, and a small retro-train. The fall colors, clouds, and the weak late-afternoon sun gave the landscape a bleak atmosphere—a fitting backdrop for exploration of a medieval place.

English countryside to the south of Bodiam. The French army—or any other continental enemy—would have appeared on this horizon. ©Libor Pospisil.

I gazed toward the south, where the castle defenders would have expected the French army to appear from behind the horizon. The expectation that an enemy would pass through this territory, on their march from the south, did not fade away with the Middle Ages, however—in the 1940’s, a pillar box was built near the castle to provide a place of resistance against a potential German invasion.

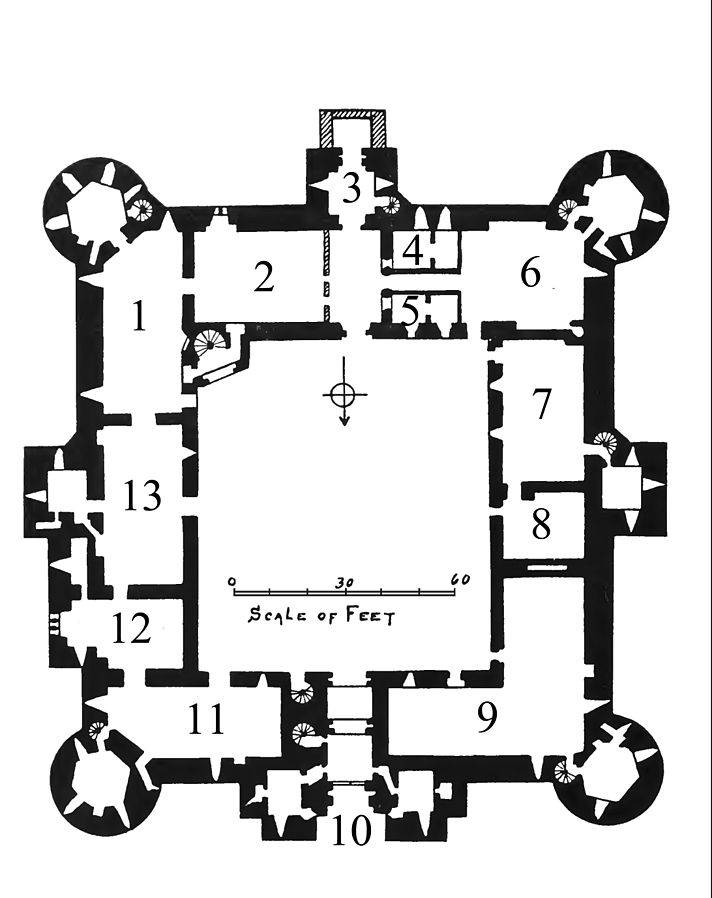

Upon returning to the courtyard, I began to inspect the remains of the walls that used separate the chambers of the castle. The life in the castle was neatly organized along the four sides of its squared plan. The first side contained the Great Hall for feasts and entertaining the guests, as well as the kitchen with a well; the second side housed the retainers; the third side accommodated the guards and the horses; and the fourth side included the Chapel and Sir Edward’s private quarters.

The castle was as showy on the inside as on the outside. The interior boasted 33 fireplaces—more than comparable dwellings back then—and 28 toilets that get highlighted in all books about the castle. The authors of such books almost gleefully crush romantic readers’ idea of a castle life by pointing out that the content of the toilets used to go right down into that picturesque moat.

A plan of Bodiam Castle: 2. Great Hall; 3. postern tower; 6. kitchen; 7.-8. Retainers’ quarters; 9.-10. Gatehouse (entrance), guards’ rooms and stables; 12. Chapel; 13. Sir Edward’s private quarters.

The most preserved wall in the courtyard. It gives us the idea of what the castle looked like in its full glory. Kitchen and pantry used to be behind this wall. ©Libor Pospisil.

Left: Guards’ room, with one of the 33 fireplaces that the castle boasted. Right: A comfort zone in the castle—one of the many. ©Libor Pospisil.

Left: Looking up through the kitchen tower. The wooden ledges at the top used to serve as dovecote. Right: The well at the bottom of the kitchen tower. ©Libor Pospisil.

Where is the castle?

The castle actually looked too comfortable to be a castle. Some researchers began to question whether Sir Edward really wanted to defend “…the adjacent country,” or whether he used the threat of invasion to build himself a nice house with sham defensive features. Although the ceiling above the entrance did have murder-holes (for pouring boiling liquids on the heads of invading enemy), the castle walls, while imposing, were not that strong. The exterior windows were dangerously large and the moat could have been easily emptied by unplugging a pipe.

Murder-holes above the entrance gate—the defenders of the castle could pour boiling liquids on enemies trying to get in. ©Libor Pospisil.

While we do not know Sir Edward’s intentions regarding the defenses, he clearly felt that he had to be at least seen as having something like a castle, to confirm his status as a new member of the upper class.

What makes Bodiam stand out, however, is that elegant architectural style. Sir Edward did not want to own just a comfortable home, but an elegant one to boot.

What do we think of when we see the symmetry and those round towers? That the castle looks… “very French,” to quote Mrs. Fairfax from Jane Eyre, who would use the adjective to refer to anything that pleased one’s senses.

Sir Edward indeed got the inspiration for his castle in France, where he thus not only gained his fortune, but also a sense of style—in contrast to aristocrats who had never left the country. No records of his motivation have survived, so we can only speculate whether he dismissed thick walls and arrow slits because he thought that the French invading army could be stopped by simply putting French elegance in its way.

Castles, but with living rooms

Bodiam transports us back to the cusp of two major eras. Gone were the times when only kings could dazzle the country with their real estate, which, anyways, usually prioritized defensive features at the expense of coziness or elegance.

Gradually, toward the end of the 14th century, a lower-level aristocrat could climb to the top of the social pyramid, amass a fortune, and build himself a fairy-tale castle. The owner’s comfort, moreover, became the most important objective of the design. The Gothic era was thrown out into the moat and the Renaissance entered through the gate.

As I was leaving the castle, I realized we could see Bodiam also as a precursor to the 19th century Romanticism and Gothic Revival Style: the castle-like features that do not function as real defenses, but recall the glorious era of knights and chivalry.

It seems that Sir Edward actually wanted to build a place that would top the list of English castles, and despite being an offshoot of an unremarkable family tree, he managed to accomplish just that.

At the Castle Inn, outside of the gate, I ordered a car service that took me to a small train station in Robetsbridge, a small town four miles (seven kilometers) away. A train to London was supposed to depart only in half an hour. I therefore took a short walk down the high street of Robertsbridge, lined up with cute half-timbered houses. Although in England, even a house is not just a house—it is its owner’s little fairy-tale castle.

Additional information about the trip:

- Bodiam Castle lies about 55 miles (90 kilometers) south of London, in the county of East Sussex.

- The nearest train stations, Robertsbridge and Royal Tunbridge Wells, are served by Southeastern Railways, with timetables available at https://www.southeasternrailway.co.uk/timetables.

- The opening times and information about the castle can be found at https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/bodiam-castle.