After exploring the desert at Sossusvlei, described in Part 2 of the Namibia series, I continued further south to reach the Fish River Canyon. The canyon and its dimensions were impressive, but I ended up being even more fascinated by other, uniquely Namibian landscapes, which I discovered along the way.

* * * * *

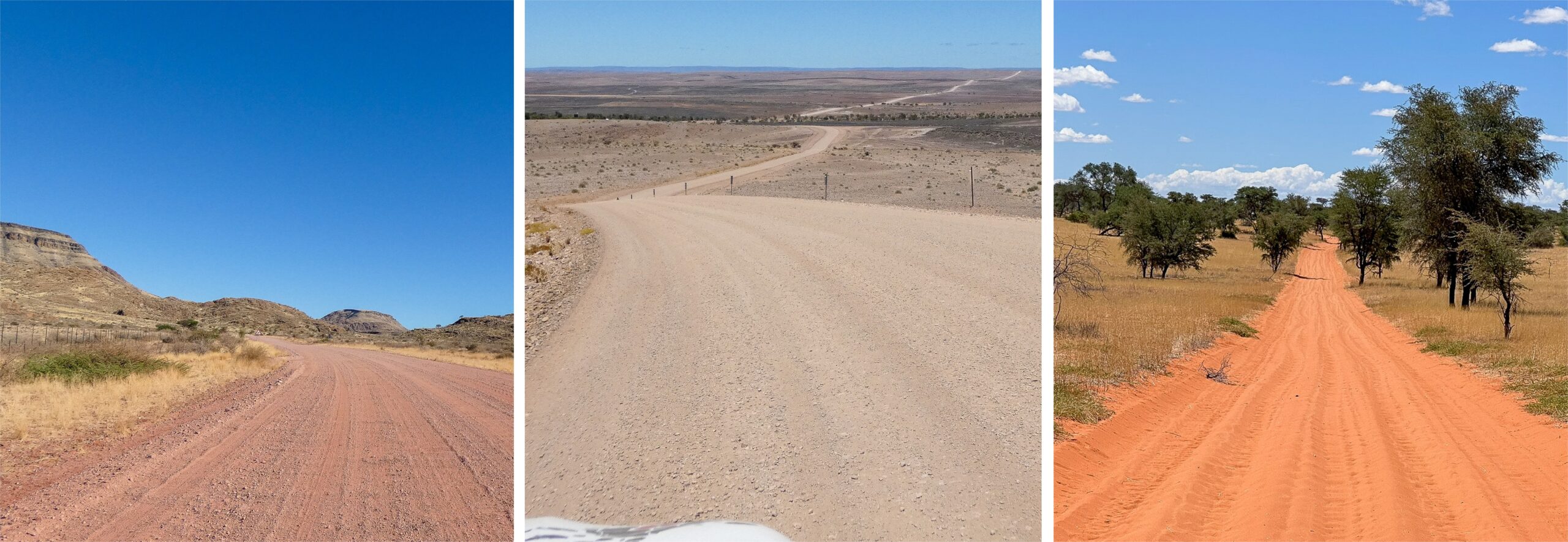

It was one of the days when I had to drive for long hundreds of miles. The sandy desert of Sossusvlei receded, and colorful rocks appeared. It reminded me of the American Southwest again.

Namibian forest

As a break from the endless driving, I stopped outside the town of Keetmanshoop and took a walk in a small desert park. It was no ordinary park, however, thanks to its rare cluster of Quiver Trees, a very Namibian sight.

Quiver Trees are a subspecies of aloe that survives only in a few spots across southwestern Africa. All of them look remarkably similar. The trees have bare trunks that suddenly split into dozens of branches pointing upwards, ending with little green leaves. Their majestic regularity contrasts with the craggy terrain that they grow on. They resemble a quiver full of arrows, which, intriguingly enough, is not just an imagination. The San people of Namibia used to cut branches of Quiver Trees and turned them into cases for their arrows. That is, apparently, how the trees got their name.

Quiver Trees are associated with Namibia so closely that they could compete with Deadvlei for the most iconic image of the country. That image is even more striking at night. If a visitor gets a permit in advance, they can stay at a campsite adjacent to the Quiver Tree Forest. When the sun goes down, they can try to take their own version of the beautiful photograph that has Quiver Trees against the starry sky. For some visitors, such a moment becomes the photographic highlight of their trip. In fact, there is a niche way of exploring Namibia, offered by several travel agencies — a two-week photography tour, which takes visitors and their cameras to the extraordinarily scenic spots around the country.

A crowded place in the desert country

Close to the forest is Giant’s Playground, another place for a short walk. It has oversized boulders stacked into gravity-defying formations. I took a quick peek and then headed for a large service station to refuel the car and get more supplies before leaving Keetmanshoop. Such stops are no mundane activity in Namibia, but an all-important part of planning given how far apart services can be located.

At the service station, I found myself in a different world. The deserts and solitude were gone. Instead, I zig zagged among humming cars, trailers, buses, and streams of travelers lining up to get fast-food meals. Keetmanshoop may be a small town, but it is the major intersection of the south. Many tourists crowding the station entered Namibia from the country’s southern neighbor. Keetmanshoop lies closer to that border than to Windhoek. The tourists usually stay in the parks and resorts in the south, including at the Fish River Canyon, where I was going next too.

I did not need to worry about crowds. The country is so immense that on the way out of Keetmanshoop, clusters of cars quickly dispersed across the empty landscape. My drive was slow, moreover. I made a detour to inspect the upper stream of the Fish River, before it reached the canyon. Up there, the river carved just a shallow gap, and its water seemed dried up and vanished in the December heat.

My next stop was unplanned. I noticed an old-time ranch on the side of the gravel road. It offered coffee, Namibian steaks, and German apfelstrudel. The decades-old rusty cars, used as decoration, amplified the vibes of a bygone era. In the south, the names of settlements are more commonly German too — from Mariental down, there is Grünau, Lüderitz, and Karasburg. The arid region was always sparsely populated, even before the genocide that decimated the Nama people who used to live there. A lot of new places therefore received European designations. The big towns of the north, on the other hand — Rundu, Oshakati, Otjiwarongo, Tsumeb — have almost exclusively names from African languages.

Close to the canyon, the road passes through Gondwana Nature Park, where I pulled over and took pictures of ostriches freely running around. When I finally reached the lodge, I saw it was buzzing with patrons, some of whom I thought I had met at the service station in Keetmanshoop. They were enjoying their dinners and beers.

Ocean of rock

First thing in the morning, I drove to the Fish River Canyon and took a short hike at its rim. It is possible to plan a backpacking hike along the river at the bottom of the canyon. That hike is strenuous, involving eighty kilometers (fifty miles) of walking, and always requires an authorized guide. December, with its summer heat, was not the month for it — the canyon administration operates those hikes only from May to September.

The statistics of the Fish River Canyon are staggering. It is over 160 kilometers long (100 miles), up to 27 kilometers wide (17 miles), and 550 meters deep (1800 feet). Based on some of these metrics, it is the second largest canyon in the world after the Grand Canyon, and it is undoubtedly the largest one in Africa.

The visual spectacle more than matches the statistics. From the rim, I kept staring deep down at the meanders of the Fish River, far below the layers of rocks in brown, orange, and grey. The occasional bush or cactus only emphasized how barren the landscape was. I walked from one scenic viewpoint to another, enjoying the same thrill of remoteness as in the other deserts of Namibia. A car honking in the distance did not change that. They just assumed I was lost and needed help. I waved thumbs-up and had the canyon to myself again.

The Fish River Canyon, however, suffers in the eyes of us, who have visited the Grand Canyon. The Namibian smaller sibling is a true natural wonder, and it is beautiful. But unlike the sand deserts of Namibia, it looks familiar. Add to it the beer-drinking vacationers in the lodge, and I began to crave one last dose of an undisturbed, distinctly Namibian place. I was happy to find it the next day as I was driving back north.

A desert full of life

At Mariental, I left the main road again and, this time, headed east, into the Kalahari Desert. There, the landscapes were mild, with no rugged mountains on the horizon. The gravel road passed by private reserves, and I stopped outside one of them to observe a family of giraffes munching on bushes. I did not need to go on safari; the giraffes were right there by the road, behind the fence. The other animals, the desert termites, might not have been visible, but I knew they were around thanks to their tall mounds of soil, which lined up the road like signposts.

I arrived at the last destination of my trip, a small lodge in the Kalahari, which had a mercifully low occupancy. I spoke to the gentleman, who let me in. He moved there from the north, and his language was RuKwangali. He taught me to say thank you as “Mpandu,” which was easy enough to pronounce.

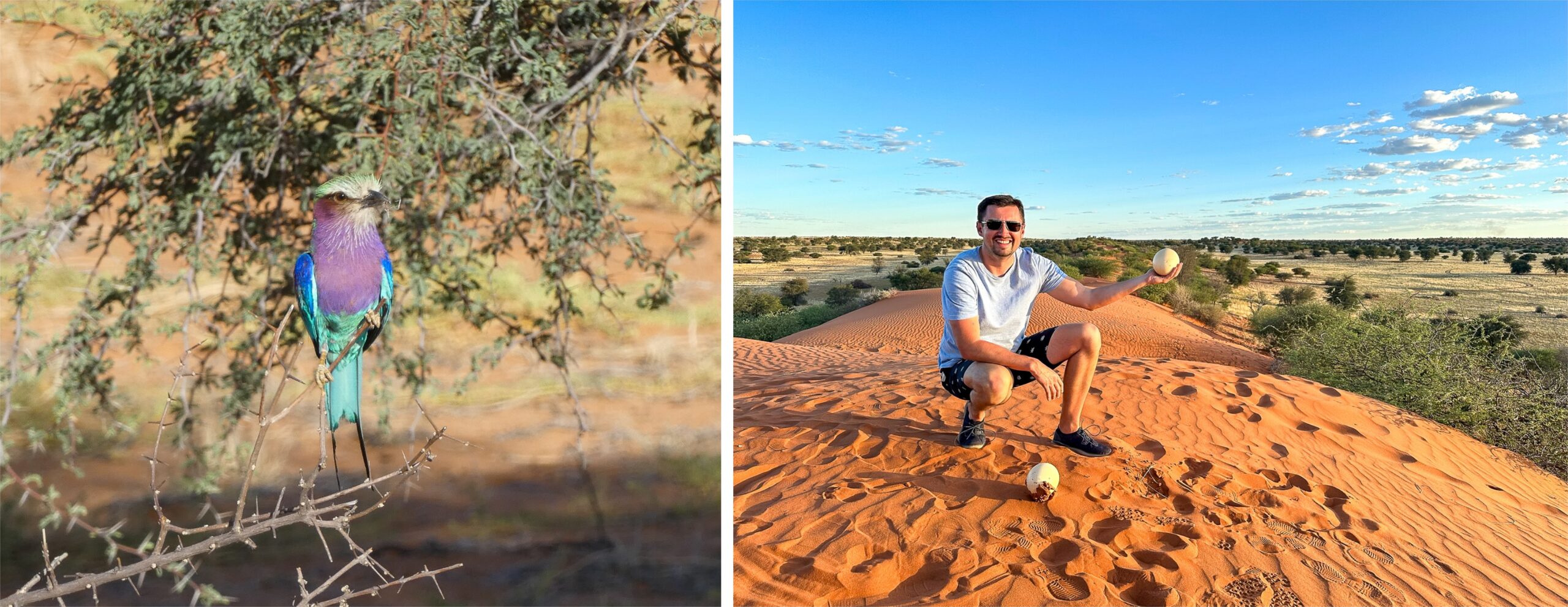

Toward the evening, Ivan, one of the rangers at the lodge, took me on a ride in his jeep into the desert. We followed rough, red, sandy tracks, which bounced us up and down like a roller coaster. We saw herds of animals, zebras and ostriches, and then a bird, a lilac-breasted roller, whose feathers looked unusually colored to me. I learned, however, it was a common species in that part of the country.

We stopped at the top of a hill to look around. The scenery of the Kalahari was so different from what I had previously seen on the trip. This desert was made of long, linear waves of red sand, and unlike in the Namib desert, there were no extreme dunes. The Kalahari gets some amount of rain, however small, which means that grass can grow from the sand. The shallow valleys between the waves even sustain bushes and occasional trees. The vegetation anchors the wavy dunes in place and prevents the wind from moving them easily. Animals can, therefore, make their home in the Kalahari, and, suddenly, the desert is full of life.

After the severe landscapes of the previous days, I began to appreciate the mildness of the Kalahari. The light of the sunset helped; it made the red color of the sand radiate through the grasses. Not far from where we stood, I noticed ostrich eggs. Ivan identified them as abandoned and thus safe to hold, which I did.

Can you say ostrich egg?

Ivan mentioned that he grew up in the area and that Nama was his first language, which piqued my interest. In Namibia, there are two broad families of languages. Firstly, Nama and San (also known as the Bushmen language). Those are spoken by the very original inhabitants of the land, now living primarily in the center and the south. Nama and San languages are called “click languages” thanks to their unique sounds that resemble clicking or popping. In the country’s northern half, people use languages from the Bantu family, including Oshiwambo, Herero, RuKwangali, and others, which were brought there by pastoralists who began migrating to the country’s territory from central Africa in the 14th century. The distinction between the two families is a bit complicated, however, since in a linguistic fusion, RuKwangali adopted some of the clicking sounds from Nama.

I asked Ivan how he would say, for instance, “ostrich egg” in Nama, which he was holding in his hand. “/Amis !upus,” he said clearly, using the click sound in the place of the exclamation mark. I tried to repeat, but my tongue could not do it. Then he said it in the San language, in which the phrase has two clicks. At that point, I called off the language lesson.

Surviving in the desert

In the morning, four young men arrived at the lodge on a pickup truck. They jumped off and changed into traditional bushmen attire of leather cloth and headband. They were members of a San group from a nearby village, which reenacted the hunting lives of their ancestors. For authenticity, they spoke to me and the few fellow guests only in the San language. Their leader provided some commentary in English, but only after making us guess what was going on.

The guys led us along a path into the desert. They stopped at one bush and pointed to a solitary straw sticking out of the sand. With their hands, they removed the sand around the straw and showed us, victoriously, the ostrich egg that was buried there. They had, of course, buried the egg there before, which was what their ancestors would have done. They used empty ostrich eggs as jars, which they would fill with water and hide them carefully along their lengthy hunting routes. The straw sticking out of the ground was their method of geolocation.

We came to a termite mound where one of the group members descriptively gesticulated toward its base. Termite mounds were a good place for hunting since termites served as food for aardvarks, and aardvark meat used to be on the San menu. The hunters devised ingenious ways to trap the animal because despite its small size, aardvark can be aggressive and knows how to use its sharp claws. The leader was pleased with the detailed demonstration of the hunt: “The guys are great! I think we should go on a tour around the world with this.”

“Are there still any San people that live completely as hunters?” was the last question to the leader. The 1980 movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, with its romanticized view of Africa, suggested some still did, at least recently. “No, no one does. Not in Namibia. To live like this, even a small group of people needs to keep moving across a large territory. But there are too many ranches with fences now, and we have droughts. And people have other options. Those who stayed just settled. Why should you hunt for an antelope for two days when you can get a steak in Spar in town in two minutes?”

Capricorn

I left the lodge, saying “Mpandu” to the gentleman at the gate. “Aah! You remember!” “Well, I could remember the RuKwangali word. But I am not able to pronounce anything in Nama.”

Like the rest of the country, I went to Spar again, to buy supplies for the last stretch of the journey back to Windhoek. Afterward, I drove for some time until I reached a road sign that could easily be missed, despite its significance. It marked the Tropic of Capricorn that runs through Namibia. Coincidentally, it was late December, noon time. I had a lunch picnic there, right at the sign, while the sunrays were pointing directly onto my head from above.

After being waved at the last checkpoint, I arrived in Windhoek. There, I returned the car with sadness. The same car I had not even wanted to rent. I came to Namibia to hire a driver to take me to the rocky canyons. Instead, I moved around on my own and walked on sand dunes. I came for solitude, and I got it; it just included my own planning and responsibility for everything on this trip.

Then, I remembered the unexpected beauty of Namibian landscapes. They left me speechless, which must happen to anyone who sees them for the first time. Although, even if I was eager to talk, there was mostly no one to talk to. I met only a few people on the endless gravel roads and at the remote desert vistas. That made me even more grateful for the occasional conversation with any Namibian I encountered.

I boarded the evening flight at Windhoek airport with reluctance. I did not want to let go of the thrills of this trip. As we took off, I was quietly watching the sky from the airplane window. With sunset over, the sky turned purple again. That was the most wonderful sendoff I could have asked for.

If you go

Around Keetmanshoop: Quiver Tree Forest https://gondwana-collection.com/blog/where-is-the-quiver-tree-forest-in-namibia; Giant’s Playground https://gondwana-collection.com/blog/what-is-the-giants-playground-in-namibia; Quiver Tree Forest campsite — here, you get tickets for both Quiver Tree Forest and Giant’s Playground https://www.quivertreeforest.com/home

Fish River Canyon: Gondwana Canyon Park outside the canyon, with free-roaming animals https://www.info-namibia.com/activities-and-places-of-interest/fish-river/gondwana-canyon-park; visitor information about the Fish River Canyon https://gondwana-collection.com/en/the-fish-river-canyon-experience; about hiking the canyon floor https://www.nwrnamibia.com/how-to-book-fish-river-canyon.htm

Kalahari Desert: among the many lodges in the desert, this is the one, where I stayed https://the-elegant-collection.com/desert-lodge.html

This article was previously published on TravelExaminer.net, where you can view dozens of award-winning national and international travel destination articles: