In the first part of this Namibia series, I explore Windhoek, and I travel to the country’s coastal desert. There lies the old resort town of Swakopmund. Then, it is just a short drive to Sandwich Harbour, the only place on Earth where gigantic dunes fall straight into the ocean.

* * * * *

This trip began when the screensaver on my laptop randomly chose a beautiful photograph of what looked like the Grand Canyon. The warm colors of the rocks and the barren landscapes made the scene extremely reminiscent of the national parks in the American Southwest. For some of us who grew up surrounded by fields and forests, the pull of the desert is irresistible. We call them otherworldly, not just as a turn of phrase. At closer inspection, however, the picture was a canyon on the other side of the planet — the Fish River Canyon in Namibia, a country in southern Africa.

Soon enough, I found myself on a plane landing at the airport outside Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. At that moment, I had no idea that the Fish River Canyon would be overshadowed by the country’s other deserts, which I ended up ranking among the most spectacular landscapes in the world.

Windy corner

Windhoek was nowhere to be seen from the plane. Only rugged mountains and dry savannah were in view. It took a half an hour of fast drive to reach the city’s edge. One theory says that Windhoek got its name from “Windy Corner” in Afrikaans, so the airport was purposely built in a safe distance from the city itself. I recalled this weather reference one more time, when I experienced a summer wind storm in Windhoek (in December), with branches of trees flying and landing on the road.

The empty grasslands on the way to the city was a neat illustration of the key fact about Namibia — it covers territory twice as large as California or Germany but has only three million people. Namibia is the second most sparsely populated country in the world, right behind Mongolia. The ride to Windhoek was just one sample of the country’s isolated geography. Much more was to come.

I had a day to explore Windhoek before my first desert trip. The downtown is pleasant to walk around, with remnants of German colonial architecture, including a church (Christuskirche), a fortress (Alte Feste), and the parliament building (Tintenpalast). Also, in the downtown, there is the harrowing memorial to the genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples that took place during the colonial era.

After stopping at the Namibia Craft Center, I visited the tallest new structure in Windhoek, the Independence Memorial Museum. It was built by North Korea in 2014, before its companies had to leave because of U.N. sanctions. The abstract shape of the museum edifice does not look too abstract to the locals, who refer to it as the “Coffee Maker.” Its exhibit and murals are dedicated to Namibia’s march toward independence, from Germany and South Africa, which it achieved in 1990.

Namibian purple

At the top of the museum is a restaurant with a viewing terrace, which I used as the place for a meaty dinner. Julia, a lady having a drink there, struck up a conversation with me. Like others I spoke to in Windhoek, she moved to the city from the very north of Namibia. I asked her about local languages, and she taught me to use “tangi” as “thank you” in Oshiwambo. This is the most widely spoken language in the country, concentrated chiefly in the north. Although reflecting Namibia’s history, “tangi” is a loan-word, based on the Afrikaans “dankie.”

Julia even spoke some Portuguese because her hometown was located on the Angolan border. That association was familiar to me since a gentleman in Windhoek had told me earlier how he played soccer in northern Namibia with boys from the neighboring Angolan village.

We were looking over Windhoek together. It is a mid-sized city, and beyond the surrounding mountains, there is nothing, just vast spaces. The nearest million-size metropolis lies thousands of miles away.

Julia was telling me about her trips to Europe, not paying attention to the sunset, of which I was ferociously taking pictures. The layer of vivid purple, hovering above the silhouette of the mountains, might have been an everyday sight for her, but I fall for the African sunset every time.

It is no accident that many people in Windhoek are northerners. The north of Namibia is the most populated region — meaning least sparse — because it is the least dry one. It is the only region with enough rain to sustain cattle and game. The north has the Etosha National Park, home to the iconic big five species of African animals. No wonder Etosha is a popular safari stop for tourists on their grand tour of the country. The rest of Namibia can offer only mountains, deserts, and dry grasslands, which is exactly where I was headed next.

Out of the city and toward the coast

From Windhoek, I traveled in a crowded van serving as public transit. The ride went on for about four hours. Despite the sleep-inducing straight road, I managed to wake up to the sight of a train, fuming heavy black smoke, as it carried freight between the ocean and the interior. The monotony of the landscapes was interrupted only by the rocky domes of a formation called Spitzkoppe, a place for hiking and camping.

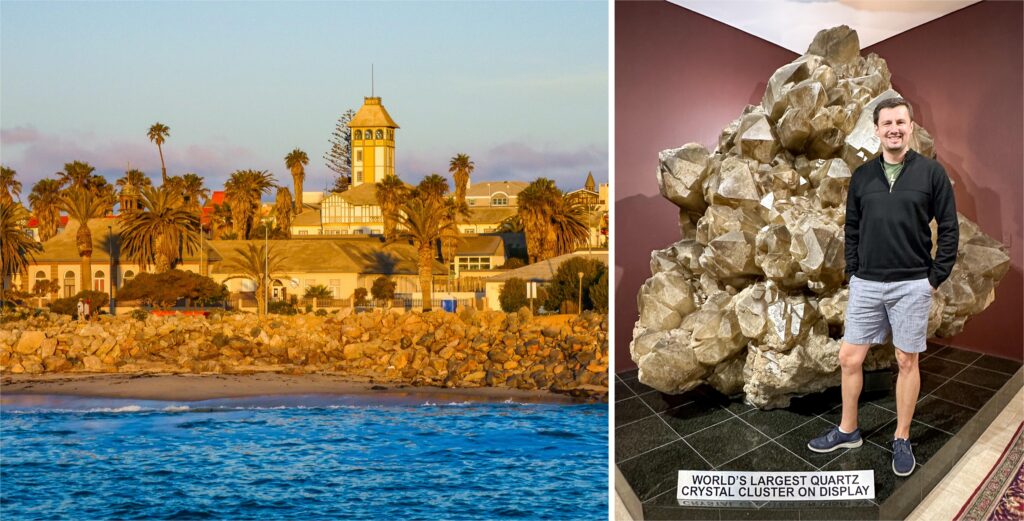

Eventually, the grassland yielded to sand, and then the Atlantic Ocean appeared on the horizon. We finally made it to the coastal town of Swakopmund, whose name means “the Mouth of the [River] Swakop” in German, even though the river’s name itself comes from the Nama language. I walked the geometrically laid-out streets of Swakopmund and hoped for the salty fog to disappear. When it did, I admired the purest German architecture of the southern hemisphere. Timbered houses, an ornate former train station, and the several crenelated hotels all looked cozy. The yellow façade of the neo-baroque church almost transported me to central Europe until I noticed the palm tree beside it.

Swakopmund is a proper coastal town with a lighthouse dressed in red and white. The museum next to the lighthouse and the antique shops found all over the city have plenty of furniture, machines, and everyday items that took me back to the 19th-century world of the German settlers. There is more to see in the museum, however — weapons and pottery of the iron-age native peoples and reproductions of their rock paintings.

A few steps away, in the richly supplied Kristall Galerie, I found a unique exhibit of Namibia’s gems and crystals. Among its stunning pieces was the largest cluster of quartz in the world, taller than I; it was discovered not far from Spitzkoppe only in 1985.

Today, Swakopmund is the favorite place for European vacationers in Namibia, pensioners and digital nomads alike. Although I was not thrilled with its resort-like atmosphere, I took advantage of the resulting multitude of good seafood restaurants. They serve local catch, of course, with kingklip being the most unique and popular fish.

Sand and water

I was happy to leave Swakopmund on a day tour to Sandwich Harbour. Little did I know it would turn into a spectacular highlight of the whole trip. The driver, José, was a Namibian despite his Spanish name. He picked me up in his jeep, and once we passed the port of Walvis Bay, the intriguing part began. José started lightly. He showed me a flamingo herd and a pink lake, which got its color from a special mix of salt and algae. As we passed by low-rise coastal dunes, José remembered how he drove them down on a quad bike when he was a boy: “I never wanted to live anywhere else,” he said.

Soon we left the paved road and continued along dirt tracks, with the ocean on the right and yellow, sandy mounds on the left. José stopped at one point, got out of the car, and walked toward the mounds. Suddenly, one of his legs sunk deep into the sand: “You see! It’s a thin layer with an underground water beneath.” He pulled his leg back, and it was dripping wet. He described how people driving the area on their own often get stuck, with a wheel cracking through the crust layer.

José then inspected creases in the sand, the purpose of which became apparent when he pulled a little lizard from it. He affectionately held it in his hand and showed it to me. The lizard — Namibian sand gecko — was almost transparent. “Why are you holding your other hand over it?” I asked. “Look how sensitive it is to light. And look at the big eyes. It needs them late at night to search for food. When I put it back on the sand, it will immediately dig its way inside.” So it did.

We drove farther out, left the dirt tracks behind, and found ourselves among sandy dunes. Up and down and over, José enjoyed showing his sand driving skills, accelerating dramatically as we neared the edge of the last dune before the ocean. Had he not turned sharply, we would have been flying into the water. I tried not to give him the fun-scared tourist reaction, but even I cracked at that speed. He then let the car just slide down a sandy slope before gearing up for the last ascent.

The end of the world

We were not on small dunes anymore. These were severe peaks of sand, over a hundred meters tall (three hundred feet). We stopped at the crest of the tallest one. José said: “Enjoy and walk down to the ocean. I will meet you there.” I stood at the top, looked around, trying to take in the view. The landscape was plain yet so unique that no other scenery in the world could match it. There was only blue and yellow in sight. Above was the clear sky, and below it, the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, with the little natural harbor. As I turned around, there was the ocean of dunes in perfect yellow, with nothing else on the horizon. The only sign of civilization was José’s car parked on the shore.

Sandwich Harbour is said to be the only place on Earth where dunes of this height go straight into the ocean. I felt overpowered, not only by the geomorphology and the visual drama. It was the air of remoteness that mesmerized me. I couldn’t get enough of it. Sandwich Harbour is a true desert, far from Windhoek, let alone any metropolis. Unlike deserts in the northern hemisphere, there was never a major trading route here, just a minor one. No caravans of camels would pass by. Even the European ships that once sailed around Africa were not welcomed here. The northern Namibian shore is called the Skeleton Coast. On its beaches lie bones of whales and also the wrecks of ships that sailed too close to this forbidding land.

As with Windhoek, we do not know the origin of the name Sandwich Harbour — it may refer to the British sailing ship, a whaler named Sandwich, that hunted in the South Atlantic in the 18th century. The remotest location, the uncertain name; it did feel like at the end of the world.

I wish I could have stayed longer there, to enjoy the desert in all possible ways. I would have just observed it, then I would have run the dunes up and down like José would have as a little boy, and certainly, I would have taken many more photographs. If I were a painter, I would have wanted to paint the scenery, impossible to find anywhere else. But the wind grew stronger, and the sand began rising from the dune’s crest. My face was stinging and I couldn’t take it much longer. I slid barefoot down the dune, toward the car. I kept stopping and looking around. José smiled at my shell shock, which he most likely sees in anyone who visits for the first time. “I have never been to a place like this,” was the only thing I could say.

Part 2 of the Namibia series

In the second part, I go on a dusty road trip to Sossusvlei, the interior desert of Namibia. There, I got to see the most iconic view of the whole country.

If you go

Windhoek: Namibia Craft Center https://www.namibiacraftcentre.com/; Namibia Independence Museum https://www.museums.com.na/museums/windhoek/independence-museum; a guided tour of downtown Windhoek and its northern township Katutura https://www.chameleonsafaris.com/; high-end dining in the former German castle, Hotel Heinitzburg https://www.heinitzburg.com/restaurant.html

Swakopmund: Swakopmund Museum https://www.museums.com.na/museums/coast/swakopmund-museum; Kristall Gallerie https://kristallgalerie.com/

Sandwich Harbour: tour company Sandwich Harbour 4×4 https://www.sandwich-harbour.com/

This article was previously published on TravelExaminer.net, where you can view dozens of award-winning national and international travel destination articles: