One summer, a ginger-bearded, shy, melancholic, thirty-seven-year-old man stood on a dirt road outside of Auvers. He held a brush and worked his canvas, painting the surrounding wheatfields.

With his relentless concentration, he might have finished the piece within a day, just as he had managed to do with previous paintings.

A few times, he got chased away from his painting spot by local boys, who saw the painter as an odd foreigner and threw stones at him. Other times, he got distracted in a more pleasant way, such as when Marguerite, a young lady with an artistic sensibility, stopped by to talk to him.

Artistic getaway

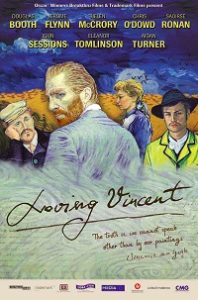

These scenes come from the 2017 movie Loving Vincent, which portrays Vincent van Gogh’s life in the town of Auvers-sur-Oise (pronounced o.vɛʁ.syʁ.waz), outside of Paris, where the artist stayed for two months in 1890.

He came to Auvers to recover his mental well-being, but ended up painting feverishly in and around the town, right until the tragic—and still mysterious—events leading to his death.

By coincidence, I saw Loving Vincent shortly before my December trip to Paris. The visuals and the plot of the movie sparked my interest in Vincent so much that I decided to take a break from Parisian parties and make the trip to Auvers.

I wanted to walk in the footsteps of the sad genius, see the scenery that had inspired him, and visit the places associated with his tragic passing.

I wanted to walk in the footsteps of the sad genius, see the scenery that had inspired him, and visit the places associated with his tragic passing.

On New Year’s Eve morning, after an hour-long journey from Paris by train, I therefore found myself on the banks of the wide river Oise. The town of Auvers stretches along the slope above the river—a perfect impressionist scene right there.

Crumpled church

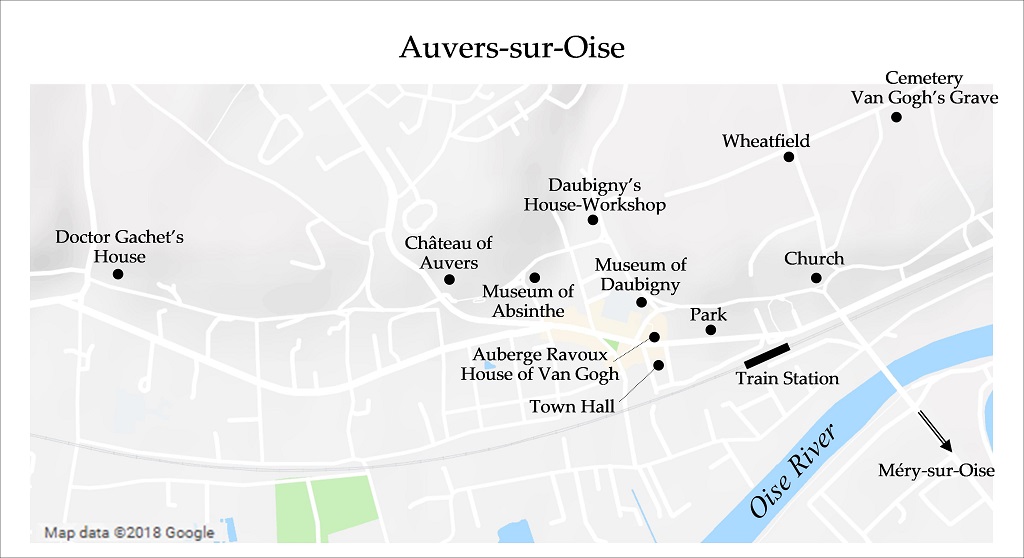

Looking around, you could immediately spot the most dominant blip in the town’s skyline: a church, naturally. I ran up the ancient steps leading to the church to see the architecture up close.

Unlike other Gothic churches, which usually almost reach the sky, the one in Auvers appears more wide than tall, as if its tower did not want to grow.

Unlike other Gothic churches, which usually almost reach the sky, the one in Auvers appears more wide than tall, as if its tower did not want to grow.

Its weighty and massive air is probably a holdover from the original Romanesque church, which left other traces on the current building as well, such as in its semicircular windows and the textbook examples of its Lombard bands.

Stepping inside, I moved sheepishly to one of the immediate corners, as I saw that the pews were filled with worshipers and mass was underway. Only after the communion had ended and everyone had left did I begin to take pictures, although my focus on the architecture was briefly interrupted by a feeling of Christmas spirit when I spotted a nativity scene.

Exquisite Romanesque architectural details (the middle picture), and views of the church’s interior. ©Libor Pospisil.

Self-portrait in front of the church in Auvers. On the far right, you can see the panel with Vincent’s painting, in which I could have ended up had I stood here in 1890. ©Libor Pospisil.

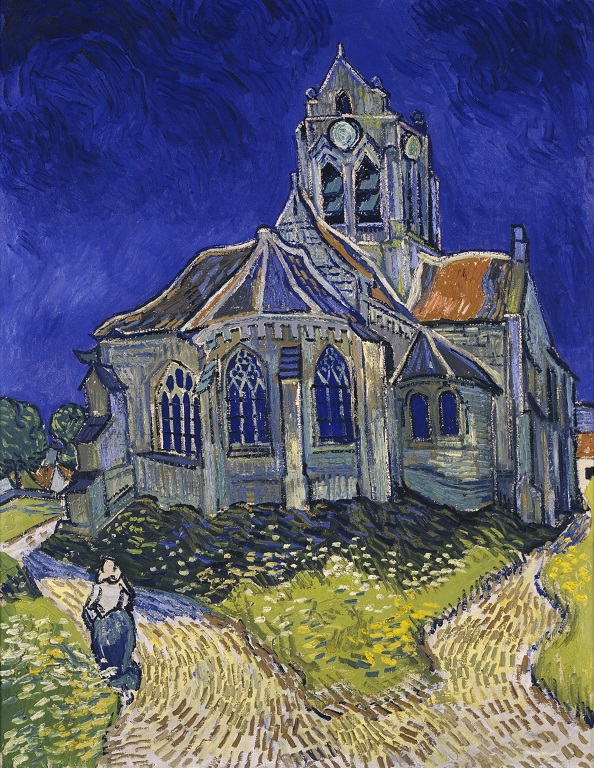

Behind the church, the first Van Gogh. The town had put up a panel with Vincent’s The Church at Auvers in the exact spot where the not-yet-famous artist—he sold just a few pieces in his lifetime—had stood and painted the church building. Thanks to this simple yet ingenious idea, you could see Vincent’s painting against the real scenery.

For some art students, coming to this spot and painting the same scenery has become an artistic pilgrimage.

I, on the other hand, engaged in a somewhat less creative activity, stepping back and forth with my camera glued to my face, trying to get the church and Vincent’s painting of the church into one frame.

While trying to get the best picture, I accidentally stomped on a plot of flowers. I was clearly not the first one to do this during a hunt for the perfect Van Goghian picture, as the plot was equipped with a placard warning people to respect the flowers—in English, no less!

The Church at Auvers painting already reminded me of a typical piece by Vincent—he made the sky bluer and the church greyer than they actually were. The straight lines of the real church became curvy and blurry thanks to his broad brush, creating the impression that the building got somehow crumpled.

Golden fields and self-doubt

On the panel with the painting of the church, I noticed a number, which, upon closer inspection, indicated that there was a trail connecting Vincent’s various painting spots in and around Auvers. I did not have time to visit all thirty panels, but I did manage to see panels in front of several famous sites. The next one I came to stood in a seemingly unremarkable spot—a dirt road passing through some muddy fields.

The spot where Vincent painted one of his wheatfield pieces. The location looks very different on a cloudy, cold, December morning. ©Libor Pospisil.

The spot, however, seemed unremarkable only because it was December; the panel that showed Vincent’s Wheatfield with Crows (Champ de blé aux corbeaux) proved that in summer, the wheatfields were glimmering gold.

As I was looking around, I imagined Vincent standing there. His typically smile-free face would have projected that perpetual self-doubt of his—Vincent was never happy with his work. Despite occasional outbursts at those whom he felt did not understand him, Vincent lived quietly, avoiding contact with people unless necessary.

Such introversion might have been reinforced by his self-acknowledged mental illnesses—the one thing everyone knows about him is that he cut off his ear. Given Vincent’s awkwardness in interacting with people around him, he became an ideal target for local rascals.

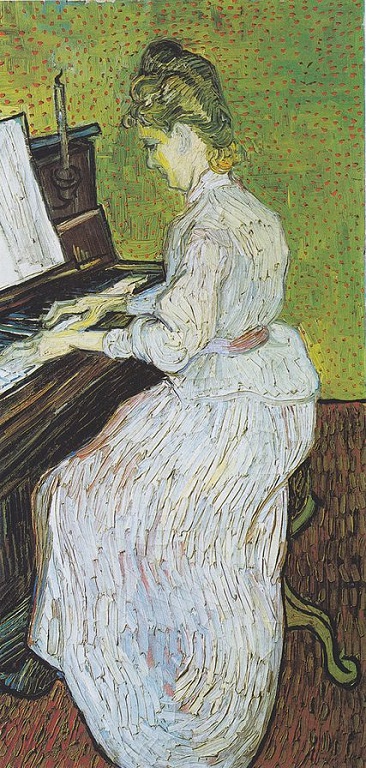

The movie Loving Vincent suggests, though, that Vincent did connect with one person—Marguerite, the daughter of Doctor Gachet from Auvers. She seems fragile and melancholic in Vincent’s paintings, which you may interpret as Vincent seeing in Marguerite his soulmate.

Yet this love story comes from a novel, The Last Van Gogh, written in 2006, and sounds too much like a cliché. It appeals to some of the artist’s admirers, mainly because it provides a convenient narrative for his tragic end.

Eternal sunflowers

Before focusing on the tragedy of the artist’s early demise, I went to the local cemetery where Vincent is buried. At the gate, a map showed where to find his grave, which turned out to be useful information, as the grave’s non-grandiosity would make it easy to miss. It was a plain plot covered with ivy—from Dr. Gachet’s house, actually—situated at the top of the cemetery, overlooking the lush valley surrounding the Oise River.

Besides the simple tombstone with Vincent’s name, there was another sign reminding me that I was standing by his grave: sunflowers, which I had not expected to see in December, not even in Auvers.

The grave had, however, not one but two tombstones—the other one dedicated to Theo van Gogh, who passed away just six months after Vincent, his brother. Even though Theo spent his last days in the Netherlands, his widow wanted to honor the brothers’ close relationship and had Theo’s body transferred to Auvers.

A direction sign in Auvers that points to the rather distant, not-so-well-known town of Zundert, 396 kilometers (246 miles) away. Located in the Netherlands (Pays – Bas), it was the Van Gogh brothers’ hometown. ©Libor Pospisil.

The Van Gogh brothers grew up together in the Netherlands and despite being younger, Theo became Vincent’s mentor for life. When restless, twenty-something-year-old Vincent did not know how to make use of his energy, it was Theo who directed him toward art.

Theo supported his brother financially, and over their lifetimes, the two exchanged 658 letters that became a priceless source of our knowledge about Vincent’s life and thoughts.

How did it happen?

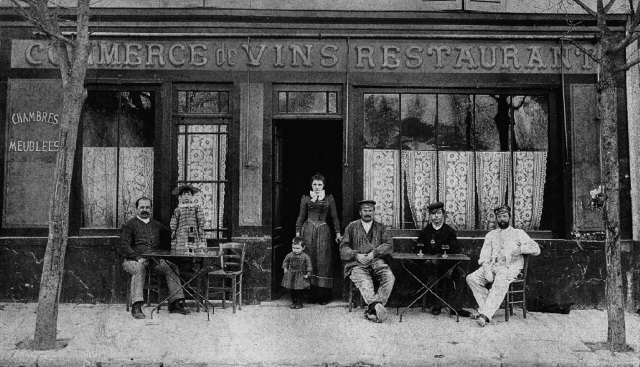

When I walked into the main square in Auvers, I easily recognized the most important building from Loving Vincent: Auberge Ravoux. It was a two-story townhouse, with the lower floor serving as a restaurant, and the upper floor, beyond a yellow façade, as an inn (auberge means inn). This is where Vincent stayed during his Auvers summer.

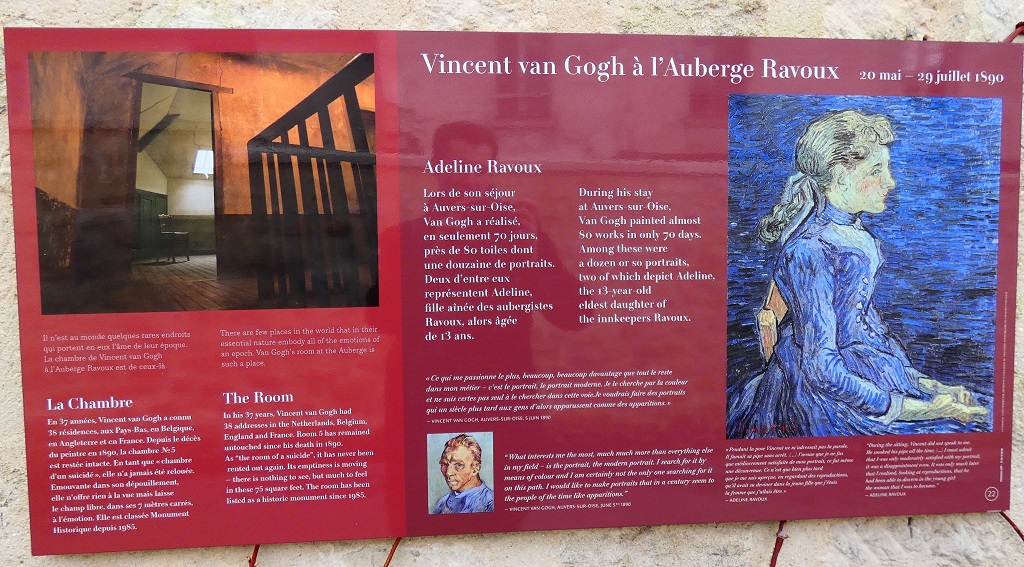

According to the movie, Adeline Ravoux, the owner’s young daughter that also ended up on Vincent’s canvass, rented a room to the arriving artist.

Vincent could not afford anything more than a small, dark room containing a bed and the plainest chair. If you choose to visit Auvers on a regular day, and not during a holiday week as I did, you can tour Auberge Ravoux—also known as the House of Van Gogh (Maison de Van Gogh)—and visit Vincent’s room. I had to content myself with trying to take a picture of the restaurant’s interior through a misty window; his table must have been in there somewhere.

I took a picture of the restaurant in Auberge Ravoux through a misty window. Vincent used to dine there. ©Libor Pospisil.

Vincent would leave Auberge Ravoux every day to look for a scene to paint. That is, until July 29, 1890, when the fateful event happened. Adeline Ravoux later provided the following account of that day in her memoirs:

…That Sunday he went out immediately after breakfast, which was unusual. At dusk he had not returned, which surprised us very much, for he was extremely correct in his relationship with us, he always kept regular meal hours. … When we saw Vincent arrive, night had fallen, it must have been about nine o’clock. Vincent walked bent, holding his stomach… [he] crossed the hall, took the staircase and climbed to his bedroom. I was witness to this scene. Vincent made such a strange impression on us that Father got up and went to the staircase … and found Vincent on his bed, laid down in a crooked position, knees up to the chin, moaning loudly: “What’s the matter,” said Father, “are you ill?” Vincent then lifted his shirt and showed him a small wound in the region of the heart. Father cried: “Malheureaux, [Unhappy man] what have you done?”

“I have tried to kill myself,” replied Van Gogh….

According to Adeline, Dr. Gachet came to check Vincent’s condition, applied a bandage, and then left. A policeman showed up next to investigate the event, but the wounded artist vehemently insisted on the suicide story.

The Ravoux family sent for Theo, who swiftly arrived from Paris, only to see his beloved brother die. The funeral service took place in the church the very next day, and Vincent’s body was laid to rest in the Auvers cemetery.

Was it suicide? And if so, can it be simply brushed aside by saying that a mentally disturbed man shot himself? No one knows for sure, which has led to a range of theories. To understand them better, I went to see a few other sites in Auvers.

Loving Auvers

I walked into the pleasant main square that Vincent could see from the restaurant’s window. The small, white town hall stood on the opposite side, accompanied by a panel showing, of course, Vincent’s painting of that classicist town hall building, in which he took the seriously straight lines and made them fuzzy, just like when he painted the church. Unlike the dusky Church at Auvers, however, The Town Hall at Auvers (La Maire de Auvers) was shown in a bright setting, depicting the square ready for Bastille Day celebrations (July 14).

Despite the wavy lines, Vincent’s piece did capture the neatness of the square. The only difference from reality I noticed was that the painting’s Bastille Day flags were replaced by the Christmas decorations I could see all around me.

After moving there, Vincent quickly became fond of Auvers. If I, as an aspiring writer, said Auvers was profoundly beautiful, I would be accused of using a cliché. Therefore, let me quote directly from a letter that Vincent sent to Theo:

After moving there, Vincent quickly became fond of Auvers. If I, as an aspiring writer, said Auvers was profoundly beautiful, I would be accused of using a cliché. Therefore, let me quote directly from a letter that Vincent sent to Theo:

…Auvers is quite beautiful, among other things a lot of old thatched roofs, which are getting rare. So I should hope that by settling down to do some canvases of this there would be a chance of recovering the expenses of my stay—for really it is profoundly beautiful, it is the real country, characteristic and picturesque…

The lack of tourists in Auvers (because of winter?) and its atmosphere of a typical French town, pleasantly surprised me since it would have been easy to turn the place into a Van Goghesque Disneyland.

I came across a lively food market and butchery, passed by some bakeries marked by the smell of fresh pastries, and saw a little girl carrying a baguette almost as tall as her.

I came across a lively food market and butchery, passed by some bakeries marked by the smell of fresh pastries, and saw a little girl carrying a baguette almost as tall as her.

I also walked by one art gallery, and when I stuck my head through the door, I noticed a balding man at his desk going through some paintings. If his remaining hair had been ginger, I would have confused him with Vincent.

In a moment, I came to the municipal park, which boasts a prominent statue. I stared at it for a moment as I was trying to figure out whether this was indeed supposed to be Vincent van Gogh. Apparently yes, at least according to the inscription. My conservative taste made me shake my head in disapproval—it would have preferred a more realistic representation of the great artist.

Statue of Vincent in the municipal park. No, unfortunately, touching the brush he holds in his hand did not turn me into an artist. ©Libor Pospisil.

Although Vincent van Gogh made Auvers world-famous, he was not the only painter that had spent time there. Charles Daubigny, who has a statue and a museum in the town, also used to live there, and we know that Paul Cézanne visited as well. No wonder Auvers calls itself the Village d’Artistes.

Village d’Artistes. Workshop (upper-left), bust (lower-left), and museum (lower-right) of another artist who used to live in Auvers: Charles-François Daubigny. ©Libor Pospisil.

The stony houses that lined the streets of Auvers preserved the old-time feel of the town. They did not appear monotonous, however—some were greyish, some more brown, and still others had edges decorated with red bricks. One of them even resembled a small French baroque palace. All were meticulously taken care of.

I then came across a stony house that had a large metal spoon hanging on its wall, which turned out to be an advertisement for the Museum of Absinthe. This museum, like many other places in Auvers, has a connection with Vincent: as is well known, the artist enjoyed a glass—or rather, a bottle—of the liquor on occasion.

I then came across a stony house that had a large metal spoon hanging on its wall, which turned out to be an advertisement for the Museum of Absinthe. This museum, like many other places in Auvers, has a connection with Vincent: as is well known, the artist enjoyed a glass—or rather, a bottle—of the liquor on occasion.

Where did it happen?

After getting out of the web of narrow streets, I emerged at the crisply manicured garden of the Château of Auvers, which itself is a perfectly rational, classicist building that now houses a museum of impressionism. Needless to say, when I was there on New Year’s Eve, the château was closed to visitors.

According to one version of Vincent’s story, he was painting on a field behind the château when he got shot. Some people question, though, whether the severely wounded painter would have been able to make it from the château to Auberge Ravoux, over a mile away.

Even if the fateful event took place there, you may be still left to ponder whether Vincent shot himself. It is certainly possible. In another Van Gogh movie, Lust for Life, starring Kirk Douglas as Vincent, it was suggested that he did it in a moment of frenzy, sparked by crows flying all around him.

Still other versions allege that the local teenagers who bullied him were the ones who pulled the trigger, perhaps by accident. This theory relies on the fact that no gun was found on the day of the tragedy and speculates that Vincent insisted on the suicide story on his deathbed because he wanted to protect the boys from murder charges.

Some fifty years later, nonetheless, a rusty gun that Vincent might have used to shoot himself was found in the field behind the château, giving the suicide story renewed credence.

Why did it happen?

A pilgrimage to Auvers would not have been complete without seeing one more building that played a role in Loving Vincent: Dr. Gachet’s house. Standing on a slope above the street, like a castle, the house also has a garden, where Dr. Gachet and Vincent used to sit at a table and talk in the evenings of that summer.

Dr. Gachet was the reason why Vincent came to Auvers in the first place since Theo recommended the doctor to his brother as someone who might help him manage his mental issues. As an amateur painter himself, moreover, the doctor enjoyed the friendship of several great artists—he knew Cézanne personally, for instance—and he apparently saw what a great talent Vincent was.

On this point, the versions of the story diverge once again. According to the novel and the movie, the doctor basically exploited Vincent, caring only about what the painter could produce, and forbidding his daughter, Marguerite, from distracting Vincent with any form of friendship. That allegedly caused a fight between the painter and the doctor, leading the unstable patient to shoot himself.

While this narrative about a love affair interrupted by a cold-hearted father sounds romantic, and it neatly explains Vincent’s death, it is really mere speculation. In fact, we know that Vincent came to like and trust the doctor as a friend and “another brother”, even if he once questioned whether Dr. Gachet’s medical procedures “…were of any use at all.”

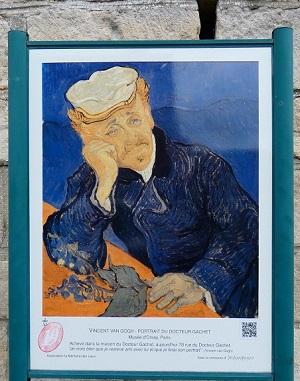

You could also try to guess the nature of their relationship by looking at a panel displaying Vincent’s Portrait of Doctor Gachet, placed at the gate of Dr. Gachet’s house. The painting captured the doctor in deep thought, almost with a sad expression on his face. No obvious trace of resentment appears in the piece.

Such a reading of the portrait is not, of course, the last word on what happened. None of us likes an open-ended story, but unfortunately, we need to accept that Vincent’s story does not have a closure. Notes by protagonists, evidence, piles of theories, romantic novels—all of those make strokes on the canvas of his last days, but the scene in the painting still remains unclear.

Before leaving Auvers, let us return to Vincent’s style one last time. In Portrait of Doctor Gachet, as well as in other portraits, Vincent did not aim to paint a photographic version of reality. He described his style, which he developed after moving to France, as a desire…

…to paint portraits which would appear after a century to people living then as apparitions. By which I mean that I do not endeavour to achieve this by a photographic resemblance, but by means of our impassioned expressions – that is to say, using our knowledge of and our modern taste for colour as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character…

Vincent not only intensified characters in his portraits but also objects in his paintings of Auvers—its buildings, roads, and fields. Walking back to the train station, I understood how the town’s pleasant ordinariness had inspired him. Before my return to Paris and its parties, I realized we had to thank the great artist for discovering Auvers for us.

Additional details about the trip

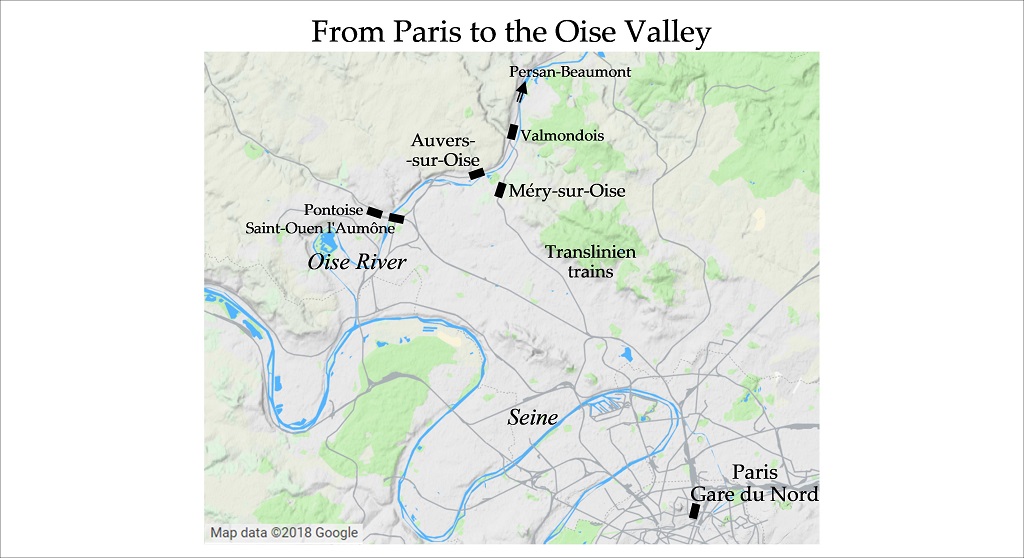

- I arrived in Auvers-sur-Oise by taking a train from Gare-du-Nord in Paris to the town of Méry-sur-Oise—a journey of about forty minutes. I then walked to Auvers, which took me twenty minutes.

- Alternatively, you can take a train all the way to Auvers, but you must make one transfer, and this route has less frequent service. The train ride from Paris to Auvers then takes about one hour.

- You can find the train timetable here.