The stretch of the Adriatic coast, where Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia meet, does not receive the same attention as Venice or Dubrovnik. Yet even a brief visit to the region reveals its unique culture and the many surprising connections it has to other parts of the world.

The Adriatic Sea is the closest sea to the heart of Europe. But its waters do not reach there, they turn around at the foothills of the Alps. The countries on the other side of the mountains are separated from the sea forever. They watch with envy how Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia enjoy the sunny beaches and the culture that emerged from the prosperous Adriatic history. When people from behind the mountains visit, they are on vacation abroad. It was not always this way.

Until the First World War, the landlocked peoples and their coastal neighbors lived in the same big polity. It was “the great and mighty empire” of Austria-Hungary, in the words of Stefan Zweig. The empire was great, but it had a different vibe than its rivals. It was terrestrial, multinational, and sleepy. Its ambitions to become a naval power were half-hearted. Still, the empire kept trying. It anxiously held on to the fragment of the coast it owned — the province of Austrian Littoral. It lied between Trieste, in present-day Italy, and Pula, at the tip of the Istrian peninsula in Croatia.

Adriatic melting pot

Thanks to this history, Trieste looks odd for an Italian city. It does have a canal with boats and a square that opens to the sea, but they are flanked by palaces of Viennese monumentality rather than Venetian elegance. Even the cafes have a distinctly Viennese feel with wooden paneling and literary histories. Trieste was the principal seaport of Austria-Hungary and its fourth-largest city, hosting traders and writers alike.

The most famous of the writers associated with Trieste was James Joyce, the Irish novelist, who moved there in 1905, to teach English. During his stay, he became a regular patron of Stella Polare, a cozy café on one of the city’s more prominent streets, where even today, you can stop for a coffee. Here in Trieste, Joyce befriended a local writer, Italo Svevo, who very well might have been the model for Leopold Bloom, the main character in Joyce’s Ulysses. In this novel, Bloom walked around Dublin for a day, which the Irish capital annually celebrates with its famous Bloomsday walk. Trieste joins in too, every June, when its James Joyce Museum organizes a Bloomsday tour of the city and illuminates the statue of the writer in green.

Among the traces of Austria-Hungary, you would still find that Trieste has the flavorful amenities of an Italian city: a popular ice cream place (Gelateria Zampolli) and pizzerias (Pizzeria Copacabana). But the unique mix of cultures is impossible to avoid. Italian, Friulian, Austrian, German, Jewish, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, and Hungarian; each of the cultures has left a mark on the city. The aforementioned Italo Svevo’s father was of German Jewish ancestry, while his mother was Italian. The lady in the antique shop, where I was buying an old map, told me her father came from Florence and her mother from Zagreb. One of Trieste’s most prominent churches at the canal is not Catholic but Orthodox, built by Serbian traders.

Two companies born in Trieste became famous around the world, carrying forward the entrepreneurial spirit of this port city. One is Generali Insurance. It prospered in the 19th century so much that Pasquale Revoltella, its Italian shareholder, was able to amass a great art collection, still on display today at the Revoltella Museum. The other company, the Illy Caffè, was founded by Ferenc Illy from Hungary, who made his way to Trieste at the tail end of the empire. Illy sparked a coffee revolution with his invention of the illetta, “a blueprint for modern espresso machines.” Illy is a global brand these days, but you can still sip it in Stella Polare.

When a castle on the sea is not enough

A short train journey from Trieste took me to the village of Miramar, where a neogothic castle sits right at the waters of the Adriatic Sea. The castle’s white colors, lean windows, crenelation, and tropical gardens make it exotic even for Italy. The castle is also cozy, with warm wood decor, an exquisite library, and sea vistas. Yet, the original owner was not happy there.

Castle Miramar was built by Archduke Maximilian, the Austrian emperor’s younger brother. Maximilian grew up in Vienna, and like any monarch’s younger sibling, he needed to find an occupation. For Maximilian, it became the command of the imperial navy in Trieste and Pula. The post did not, however, promise any glamor in an empire that lacked seafaring prowess.

Maximilian’s big ambitions went unfulfilled — until 1863, that is. That year, a delegation from Mexico visited him at Miramar. They asked him whether he had any interest in stepping in as Mexican Emperor, a position just created with the backing of French bayonets. To his detriment, Maximilian accepted and the following year, he sailed away from his castle, halfway around the world, to take up his new role. Having no understanding of Mexico’s political situation, he soon became caught up in a civil war, in which the French did not lend him the support he needed. Without their backing, Maximilian lost. He ended up being captured and executed by a firing squad. In 1868, the body of the unfortunate emperor was delivered by ship to Trieste and then buried in Vienna.

A friend from Mexico, on whose advice I visited Miramar, posed the right question: “Why the hell did the guy leave his gorgeous castle and sail to the other side of the planet to rule a country he knew nothing about?” We can find the answer in one of the ceiling frescoes at Miramar. It depicts Maximilian in an imperial robe, pointing to the heavens, while women, symbolizing continents, arts, and sciences, look up to him, full of adoration. Angels accompany the group as well. For some men, a castle with a sea view is not enough.

Languages, countries, and wines

A path leads from Miramar along vineyards to the village at the top of the hill. The village is called Prosecco. Despite the name, you would look for the bubbly prosecco wine there in vain; it is produced to the west in the Veneto region. How the wine received a name identical to the village is unclear. Legends and hypotheses abound, according to one of which prosecco grapes “have originated in the Istrian area of northern Croatia.” The village lies right between Istria and Veneto.

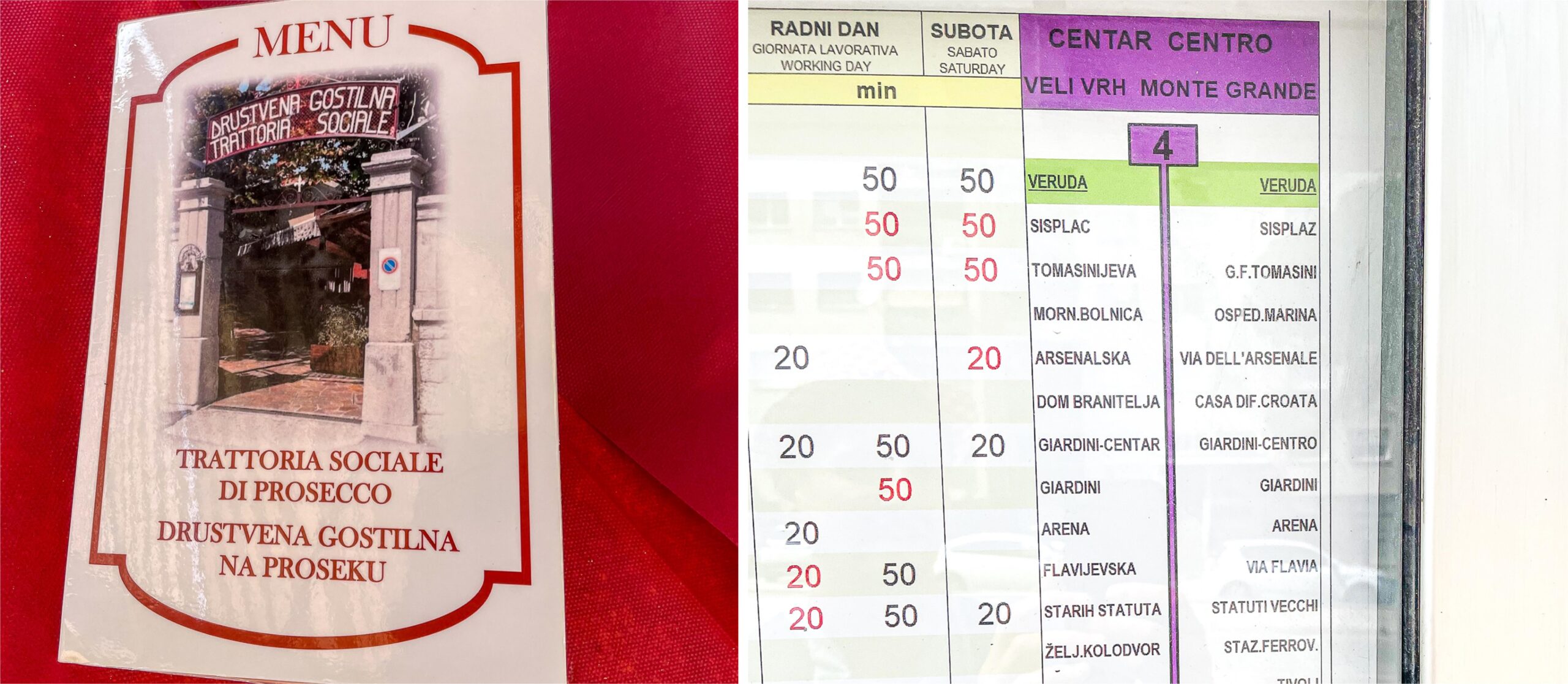

Where the name of the village itself comes from is clear, however. Prosecco is an Italian variant of the Slovene word Prosek, an ancient Slavic term for a cut-through in the woods. Slovenians still constitute a portion of the population in Prosecco and other Italian villages along the border. All the signage is bilingual here, and the local restaurant looks Alpine, with a menu in Slovenian. I ordered a non-Italian item, cevapcici, or meat rolls, with onions and potatoes. This traditional Bosnian meal became popular throughout the Balkans and the Alps. The restaurant offered a Slovenian answer to prosecco for a drink — a sparkling wine branded as Prosekar.

A walking trail from Prosecco back to Trieste meanders along the hills above the sea. Along my stroll, the clouds were deceptively thin, but as I remembered from my childhood trips to the northern Adriatic, the sun can still pierce sharply through the grey layer. It illuminated the dramatic views, with the silhouette of Miramar recognizable on the shore below. The scenery to the south is what makes the view unique. It was all Austrian Littoral in the past, but now, you can overlook three countries at once. Trieste is the last piece of Italy in the frame, followed immediately by Slovenia. However, the Slovenian coastline is short; it ends after only 30 miles (50 km). The green hills rising from the waters at the horizon already belong to Croatia. To take in even more of the view, I found the ideal perch on the terrace of the Azienda Agricola Verginella Winery. The white wine I sampled here was neither Italian nor Slovene. It was Croatian — the gold-colored Malvasia Istriana, which grows on the slopes of the hills around Prosecco.

Winged lions and a coliseum

While the Trieste region has an Austro-Slavic tinge, the coastal towns of Slovenia and Croatia look thoroughly Italian. Piran in Slovenia and Rovinj in Croatia are the two most picturesque one of them. They spread around tall, lean campaniles on a hill. They have old houses with red roofs and the Adriatic in the background. The car-free promenades along their fishing ports are enticingly dotted with seafood restaurants. To reach the campaniles, you must navigate narrow, zigzagging cobblestone streets, which contrast so much with the grandeur of Trieste. The occasional winged lion on a facade explains the heritage of the towns — they were built up by another empire, the Venetian one, which ruled these shores before the Austrians.

The connection between these towns and the Italian culture runs deep. Many of Piran’s sites are dedicated to Giuseppe Tartini, the 18th-century Italian composer and violin virtuoso who was born here. His statue dominates the main square, also named after him. Further south, in Istria, an Italian-speaking minority thrives to this day; even the local bus stops have signage in both Croatian and Italian.

The largest town in Istria is Pula. One of its central coffee shops has a James Joyce statue outside to mark the writer’s stay. Compared to Trieste, Joyce considered Pula remote and isolated (“back-of-godspeed” in Irish English). Today, Joyce’s description is unrecognizable as Pula has become a tourism powerhouse. Unlike the sandy coast of northern Italy, the beaches of Istria are covered with pebbles, which keep the waters emerald clear. Here, one finds crowds of swimmers and snorkelers during the summer months. Several beaches are in Pula itself, flanked by rental houses with sea views and restaurants serving cevapcici and seafood.

Pula offers some luxury as well, not least because Yugoslav president Josip Tito wanted to turn the town and its surrounding coastline into a window of the wealthiest communist country. The Financial Times reported on the complete remodel and reopening of the huge Tito-era Hotel Brioni in Pula, which often hosted Western stars like Sophia Loren in the 1970s.

As a former Roman port, called Pietas Iulia, Pula contains a remarkable number of well-preserved ancient sites: a Roman arch, the intact Temple of Augustus, and mosaics in the basements of current residential buildings. Most spectacularly, Pula has a Roman amphitheater, or Arena, from the 1st century AD, which is still in a good condition, despite the Venetians’ use of its stone to build a nearby church tower. At one time, the Arena hosted twenty thousand separators, about a third of the capacity of Rome’s Colosseum. Even today, the Arena is the venue for cultural events, such as Pula Music Week.

Beyond the coast

Understandably, visitors come to Istria for the sea. What they miss in the deep interior of the peninsula is a land of castles, hills, rocks, gorges, and even a fjord (Lim fjord). Some sites can be reached by a low-key train from Pula, built during the Austrian times. One of the towns along the line, Svetvinčenat, or Sanvincenti in Italian, is home to a fairy-tale-looking Venetian castle, complete with round towers. A few stops farther lies Pazin, another town with a castle, this one reminiscent of massive central European fortresses. It stands on a rock above a gorge called Pazinska Jama, which is used for ziplining these days.

The ultimate gem of Istria, the hilltop town of Motovun, lies at the end of a steep winding road. Once you reach the end of the road, you have to get out of the car and walk through the gate. Behind it, there is a web of quaint streets, a church, and an ancient castle. The feel and the views are thoroughly Venetian. Besides the scenic location, Motovun stands out for its shops selling truffle products. Although this business goes back at least a century, the town reached its truffle fame in the nineties, when the world-largest white truffle was discovered just below the hill.

Motovun may be small, yet it is prominent in Croatian culture. The legendary figure of Veli Jože (Big Joe), who symbolized the emancipation of Croatians, lived in the woods around Motovun. And then, every July, the castle and the surrounding meadows become the venue for the Motovun Film Festival, which has a decades-long tradition of showcasing independent movies, many of them Croatian.

To take the most iconic picture of Motovun, you have to make a stop among the vineyards, at the foot of the hill. Some of the vineyards belong to the Tomaz Winery, where I visited to buy a few bottles. They carry the staple red wines of Istria called Teran. And also Malvasia Istriana, the same variety I had tried in Prosecco, two borders to the north.

The two borders between Trieste and Pula are drawn on the map, but the architectural styles, the wines, and the languages spill over as if the region had no borders at all. It is a uniquely beautiful — and strategic — coastal stretch of Europe. It is, therefore, not surprising that the empires of Venetians and Austrians held on to it. The empires “vanished without a trace” from the maps, as Stefan Zweig wrote, but you can see their legacy very clearly to this day.

If you go

The following links might be helpful in planning

… Trieste: https://www.italia.it/en/friuli-venezia-giulia/trieste;

- James Joyce Museum: https://museojoycetrieste.it/en/joyce-museum-eng

- Revoltella Museum: https://museorevoltella.it/english/

- Miramar Castle: https://www.discover-trieste.it/code/16016/Miramare-castle

… Piran: https://travelslovenia.org/piran/

… Rovinj: https://www.rovinj.com/en/rovinj

… Pula: https://www.pulainfo.hr/

… Svetvinčenat: https://www.istra.hr/en/destinations/svetvincenat

… Pazin: https://www.istra.hr/en/destinations/pazin/experience/pazin-castle

… Motovun: https://www.visit-croatia.co.uk/croatia-destinations/istria/motovun/

- Film Festival: https://motovunfilmfestival.com/en/

- Winery Tomaz: https://vina-tomaz.hr/

This article was previously published on TravelExaminer.net, where you can view dozens of award-winning national and international travel destination articles.