While the Islamic-era fortress Alhambra deserves two days of attention, Granada has even more to offer — it is a city of poetry and dance, surrounded by dramatic landscapes.

Story and Photos by Libor Pospisil

It used to be hard to get to Granada. In 1829, Washington Irving described the roads as “little better than mule paths,” winding “along dizzy precipices.” Even in our century, visitors had to embark on longish rides by trains or buses since Granada sits at the feet of the Sierra Nevada mountains, in the depth of Andalusia, in southern Spain. Despite the hassle, nearly three million made the journey to Granada every year before the pandemic. They were lured, of course, by the exotic scent of the Alhambra, the Islamic-era fortress that overlooks the city. The comfort of the journey improved dramatically in 2019, when a new high-speed train arrived in Granada. The visitor numbers, which already made the Alhambra the second most visited site in Spain, were destined to grow further. But then, the pandemic struck.

In November 2021, as travel began to resume, I took advantage of the new train and packed Granada into a short Spanish itinerary. The ride itself made the trip a worthwhile experience. When the train left Madrid, it picked up speed, occasionally coasting at 300 km/h (186 mph). We cut through the fields of central Spain, and soon enough, watched the olive groves and rocky hills of Andalusia. After brisk three-and-a-half hours, spent partly in a spacious seat and partly in a bar car, we pulled into Granada. Awed by Spain’s infrastructure prowess, I tried to congratulate a local resident on the new high-speed line, but he immediately cut me short because “it took forever“ to connect his city—only the twentieth largest one in Spain!—to the rest of the country.

Whitewashed labyrinth

The Alhambra is one of those sights that visitors know they will like even before they enter. The place that charms unexpectedly in Granada is the Albaicín neighborhood, where I stayed. I dragged my luggage through its narrow streets of whitewashed houses, balconies with black lattices, terraces with lemon trees, and horseshoe gates. Gone were the wide Avenidas of the busy Madrid, gone were the gleaming façades of the wealthy Bilbao. Granada’s occasional graffiti, the chipped walls, and the little stores with Arabic crafts made it clear she does not intend to dress up to impress.

The name Albaicín sounds Arabic and like many names in Andalusia, it is. The neighborhood is popular because it shows what Granada looked like in the past and because it lies on a slope facing the Alhambra. The Albaicín has therefore many small hotels. Those willing to pay up may even snatch a room with a view of the fortress. The others need not worry. They can always walk up the cobblestone staircases, and if they do not get lost, they will find better, often surprising panoramas.

At the peak of the Albaicín, on the site of a former mosque, stands the Church of San Nicolás. Yet the crowds gathered there did not care for the Christian shrine. They look the other way, over a wall, that some adventurous young souls use as a bench. In that direction appears the most expansive view of the Alhambra, which becomes visible in its entire length of 700 meters (2,300 feet).

This Mirador, named after San Nicolás as well, could be the best vista point in the city, only if the November clouds sailed away. Somehow, they did for me, and right before the sunset. The view they opened up was better than best. The Alhambra got overshadowed by gigantic, snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada which emerged in the background. The soft evening light created golden hues in the air, with hints of red on the walls of the fortress. Since al-Hamra means red in Arabic, wouldn’t it be poetic if the sunset color gave the Alhambra its name? It would, but unfortunately, a word for red might have appeared in the name of the place “long before” the walls we see today were put up.

Lacería and mocárabes

I walked down into a ravine carved by the thin but prominent river Darro. The narrow street along its waters has restaurants, museums, and occasional musicians, making it a pleasant promenade. I, however, went on to climb up the hill to reach the fortress.

We refer to the Alhambra as a “fortress”, which is a misleading shortcut—it consists of three palaces, extensive gardens, an oversized castle, a church, ruins of a town, towers, ramparts, and paths with views in all directions. I followed the advice of a friend and planned to explore the fortress over two days. With the time saved by the train, that was possible.

The entire Alhambra usually receives praise in superlatives, but the Nasrid Palace is truly its most exquisite structure. Built in the 14th century by the Arabic sultans of the Nasrid dynasty, the palace takes us to a different era and to a different world—the world of fairytales of distant countries with effortless luxury, under the perennial sun. During the long years of construction, the sultans’ power actually began to wane. But since art often reaches its peak later than power, the sultans were still able to mobilize the skills of Muslim builders and craftsmen, to create the ultimate monument to their era.

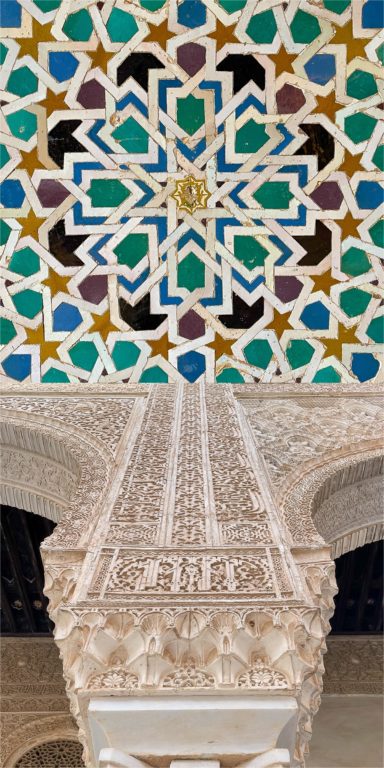

After stepping into the palace through a modest entrance, visitors are treated to a spectacle. Each hall, courtyard, and niche outdoes the previous one. The walls, inside and out, are covered by stucco and tiles, with never-ending webs of regularly zig-zagging lines. They trick the eye into seeing all kinds of geometric shapes. This decoration, called lacería, symbolizes Islamic art and features on all items in Granada’s giftshops. The ceiling art, with its three-dimensional geometry, requires a lot of head-tilting backward, but it is worth it. Some halls have ceilings made of thousands of regular drops of plaster, known as mocárabes. They create the illusion of a cave, possibly as a reference to the Islamic story of revelation, according to which the Prophet received the Quran in the Hira cave where he was meditating.

The most comfortable home

Despite the stream of visitors, ranging from art buffs to honeymoon couples, the Nasrid Palace manages to retain its atmosphere of tranquil comfort. The sound of the fountains is soothing, and the strategically placed pools reflect the architectural beauty. The mundane Albaicín lies way below, visible from safety behind horseshoe windows.

The aesthetic highlight of the palace reveals itself in the Courtyard of the Lions, in the sultan’s private quarters. The courtyard is surrounded by a veil of marble columns, and, in its middle, stand twelve lions, supporting a fountain. The Arabic poem inscribed on the fountain warns of the sultan’s powers because he grants his “war lions with favors.” The lines were written in the 14th century by Ibn Zamrak, a poet and a politician in one—a normal combination at the court in Granada.

The Hall of the Ambassadors is, on the other hand, the historical highlight of the palace. Its ceiling is about 60 feet (18.20 meters) high and contains more than eight thousand pieces of cedar wood, arranged to represent the constellations of a night sky. In its heyday, the hall beamed with all possible colors. The plaster used to be painted, and the windows were filled with stained glass. The hall served as the throne room for the sultans, who wanted to overwhelm their visitors, in which they easily succeeded.

The sultans had verses from the Quran carved into the wall, such as: “Eternity is an attribute of God.” Eternity was not, however, an attribute of the sultans, whose era was drawing to a close. In January 1492, Isabella of Castille and Ferdinand of Aragon, the monarchs of the resurgent Christian states to the north, conquered Granada, and created the Spanish kingdom as we know it today.

Coming from the world of cold-walled castles, the Christian monarchs must have felt the same awe like the rest of us when they walked through the courtyards and the halls. We know it because while they dealt brutally with the non-Christian populations of Granada, they saw no reason to touch the Alhambra. They just had some holy water sprinkled around and relabeled a mosque as a church. In fact, they turned the Nasrid Palace into their primary residence. Legend has it that in this Hall of the Ambassadors, they received Christopher Columbus when he came to seek the final approval for his voyage.

Isabella and Ferdinand grew so attached to their new capital that they chose it as their final resting place too. Today, visitors can see the tombs and the effigies of the satisfied-looking monarchs in the Royal Chapel, which stands next to the Granada Cathedral in the city center.

Into the oblivion and back

Isabella’s and Ferdinand’s grandson, Emperor Charles V, made one significant addition to the Alhambra. He invited a former pupil of Michelangelo to build him a palace glued to the Nasrid one. The result, fortunately, did not damage the Alhambra too much. Rather, it created an architectural curiosity—a high Renaissance addition right next to an Islamic palace.

When the successors of Charles V permanently moved their court to central Spain, the wealth and importance of Granada began to decline. The city was forgotten. Until the turn of the 19th century, that is, when Washington Irving, the American writer, visited and stayed in “the silent and deserted halls of the Alhambra.” He described the fortress as “dilapidated” and “desolate,” but that did not stop him from feeling inspired. His book about the trip, Tales of the Alhambra, is an engaging travelogue, peppered with dreams of a “mysterious princess” in an “Arabian romance” and with snippets of bloody events at the sultans’ court. The book became an instant global bestseller. Washington Irving, together with French romantic writers, therefore deserves credit for starting the Alhambra travel fever, which has infected us all.

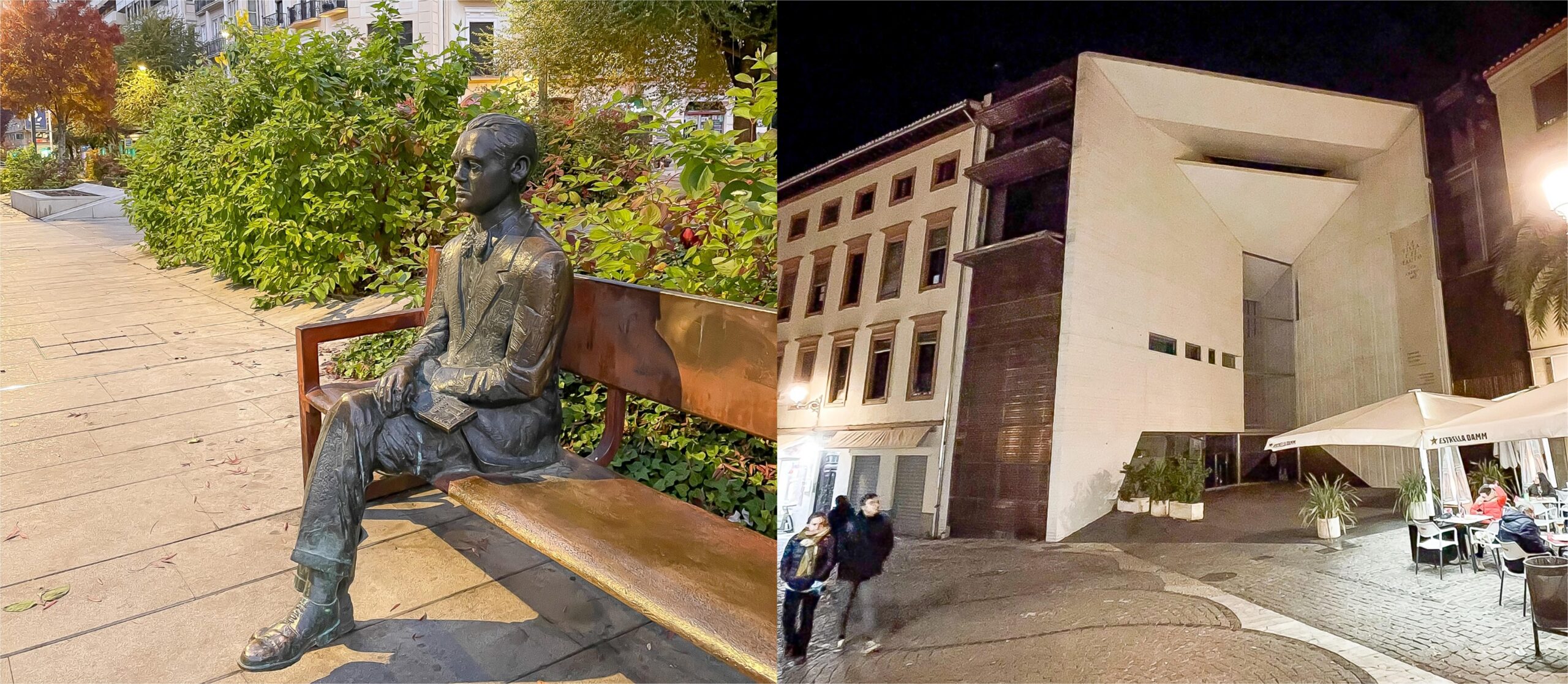

Granada is more than the Alhambra, however. Those who explore the city may feel its youthful spirit, thanks to the presence of the University of Granada. It was founded by Charles V, and now ranks as the fourth-largest one in Spain. One of the university’s alumni was Federico García Lorca, the most famous Spanish poet ever, who came from a nearby village. After his studies, he spent time in Madrid, where he passionately fell in love with his friend Salvador Dalí, and then traveled to the Americas. But he always returned to Granada, drawn to its unique culture, which permeates his work. He chose the title Diván for a book of his poems, in a nod to Arabic literature. In another book, he walks along “Arabic walls” in the Albaicín and hears “the Moorish echoes of prickly pears.”

García Lorca’s free-spiritedness was too much to handle for the nationalist forces that overran Granada in 1936 at the onset of the Civil War. Accusing the poet of “freemasonry” and “abnormal practices”, a nationalist squad took him outside the city and unsentimentally executed him. The story of his last days emerged slowly, with some documents released only several years ago. In the meantime, Granada began to proudly reclaim its famous son. García Lorca’s name adorns a large park and, since 2006, a small local airport. In 2018, the modern Centro Federico García Lorca opened near the cathedral. It houses a museum and an archive dedicated to the poet.

The sea and emotions

For a day trip out of the city, visitors can go to the Sierra Nevada mountains, for hiking or skiing. Seeing the November snow covering the peaks, I did not hesitate, rented a car, and drove straight to the warm Mediterranean coast. Federico García Lorca wrote that Granada ”sighs for the sea”, but that was true when the journey to the coast involved an arduous crossing of a mountain pass. In 2008, Spain opened A-44, a shiny and scenic highway, which shortened the trip to the beach to fifty minutes.

While on the coast, I made a stop at the village of Salobreña. I proclaim it the most beautiful village in Spain and hope that I will receive some credit for its discovery. It is not only its location on a rock between the sea and the mountains; the white houses with bougainvillea; or the castle with views. The village is peaceful. I met only a local elderly lady buying jamón ibérico in the lone shop on the plaza. And a German artist who visited the village but did not want to leave, so he set up his workshop there. A few towns down the coast, however, the old-time charm of Salobreña gradually receded to make space for bland resorts, full of vacationers and time-sharers from the colder parts of Europe. It was time to return to Granada.

I found my way back into the atmosphere of Andalusia through flamenco. I sat down in one of the theaters, initially unsure how authentic these flamenco shows would be. Fortunately, my skepticism was dispelled quickly. I saw the dancers put their lives into the performance, aimed at a predominantly Spanish audience. A young lady sitting next to me began to even shed tears, watching a dancer tap out a tragic love song. The guitarist noticed the lady’s reaction and comforted her from the stage. “That is fine, flamenco is supposed to be emocional.” My Spanish was too basic to make me cry, but that word helped me to better understand Andalusia and Granada.

Emotional, free-spirited, unpretentious, tragic, scenic, romantic—Granada is all of that. Now, after centuries of living on the periphery, the city has prospered again, thanks to the new infrastructure, investments, and rapid growth in visitor numbers. While I very much enjoy the comfort of high-speed trains and freshly paved highways, I selfishly hope that even as a tourist hub, Granada will preserve its soul. The intricate soul that accumulated such a long list of adjectives over the centuries.

This article was published previously on TravelExaminer.net (https://102.d8d.myftpupload.com/granada-spain-is-now-a-short-journey-away/).

If you go

- For a high-speed train ticket from Madrid to Granada: https://www.raileurope.com/en-us/destinations/madrid-granada-train

- The Alhambra monuments: https://www.alhambra.org/img/mapas/pdf/plano-alhambra.pdf. Make sure to see:

- the Alcazaba—the castle

- the Nasrid Palace

- the Partal courtyard and gardens

- Charles V Palace, which contains Museum of Alhambra

- the walk along the towers

- the Generalife palace and gardens.

- You can reach the Alhambra by a walk (about half an hour), taxi, or a bus (lines C30 or C32 from Plaza de Isabel la Católica).

- For the Official Alhambra tickets: bra-patronato.eshttps://tickets.alham/en/; the Tickets to the Nasrid Palace are timed and limited, so book them several days in advance.

- For information on the Museum of Federico Garcia Lorca: https://www.centrofedericogarcialorca.es/en

- Andalusia has many flamenco theaters. Here are two of them:

- Casa Del Arte Flamenco in Granada

- Tablao El Cardenal in Córdoba, which I visited.